Antitrust Issues in Generic Substitution: How Drug Companies Block Cheaper Alternatives

When you fill a prescription for a brand-name drug, you expect the pharmacist to hand you the cheapest, legally approved version-unless your doctor says otherwise. That’s the whole point of generic substitution laws. These rules let pharmacists swap a pricey brand drug for an identical, cheaper generic, saving patients and insurers billions every year. But what if the drug company makes it impossible for that swap to happen? That’s not just bad luck-it’s a legal tactic, and it’s happening more often than you think.

How Generic Substitution Is Supposed to Work

Every state in the U.S. has laws that allow pharmacists to substitute a generic drug for a brand-name one, as long as it’s approved by the FDA as bioequivalent. That means the generic has the same active ingredient, works the same way, and is just as safe. These laws exist because generics cost 80% less on average. When a brand drug’s patent expires, generics flood the market. In most cases, within months, 80 to 90% of prescriptions switch to the cheaper version. That’s how competition is supposed to work: lower prices, more access, better outcomes. But drug manufacturers have found ways to break the system-not by breaking the law, but by exploiting loopholes in how substitution works.Product Hopping: The Main Trick

The most common tactic is called product hopping. It goes like this: a brand-name drug is about to lose patent protection. Instead of letting generics take over, the company releases a new version-maybe a pill that dissolves under the tongue, or a longer-acting capsule. It’s not a major improvement. Often, it’s barely noticeable to patients. But here’s the catch: they immediately stop selling the original version. Take Namenda, a drug for Alzheimer’s. The original, Namenda IR, was an immediate-release tablet. When its patent was about to expire, the maker, Actavis, pulled it from the market and replaced it with Namenda XR, an extended-release version. They did this just 30 days before generics could legally enter. The problem? State substitution laws only apply to the exact same formulation. If the original tablet is gone, pharmacists can’t substitute a generic tablet for a capsule. Patients had to get a new prescription, and most didn’t bother. Generic manufacturers were locked out. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals called this out in 2016. They ruled that removing the original drug to block substitution wasn’t innovation-it was anti-competitive. The court said generics rely on these state laws to compete. Without them, they’re stuck.Why This Costs Billions

The financial impact isn’t theoretical. According to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), delayed generic entry through product hopping and patent manipulation has cost U.S. consumers and taxpayers over $167 billion in just three drugs: Humira, Keytruda, and Revlimid. Revlimid’s price jumped from $6,000 to $24,000 per month over two decades. That’s not because it got better. It’s because the company kept tweaking the formula, getting new patents, and pulling the old versions off shelves. Each time, they reset the clock on generic competition. In the case of Copaxone, a drug for multiple sclerosis, Teva switched from a daily injection to a three-times-a-week version. The new version didn’t work better-it just made substitution harder. The cost to patients? Between $4.3 billion and $6.5 billion over two and a half years.

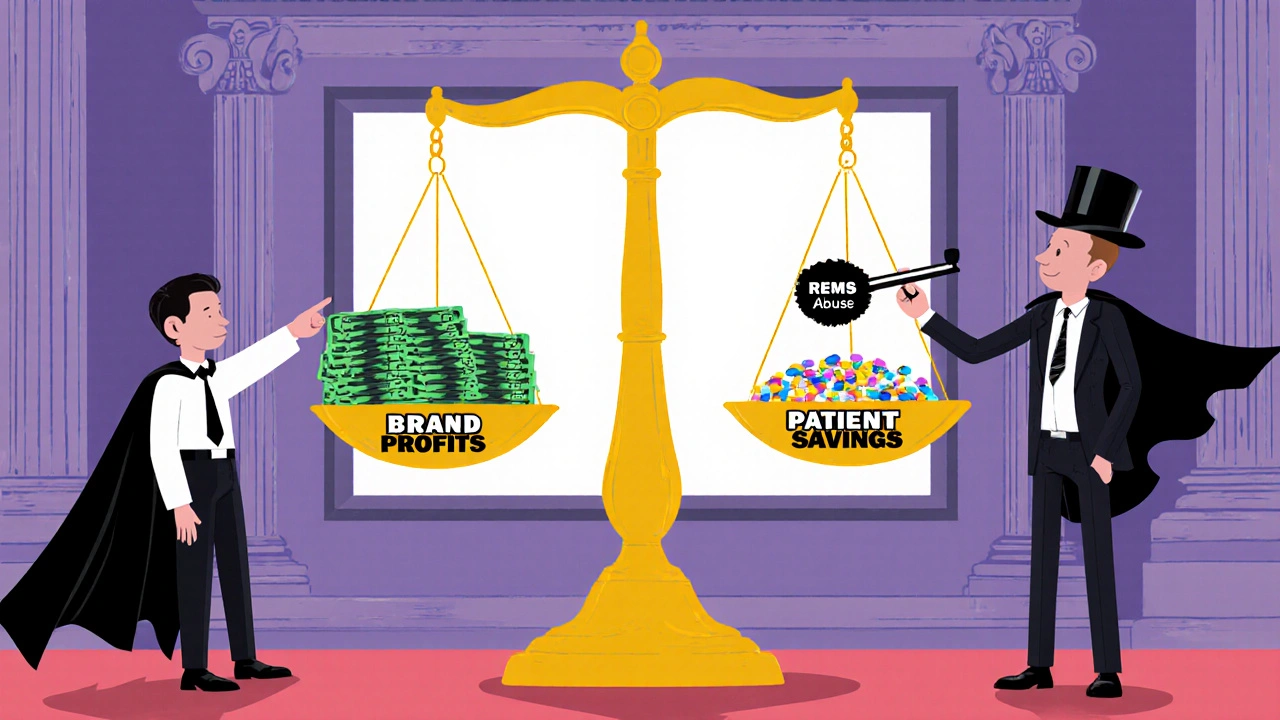

How Companies Block Generic Access

Product hopping isn’t the only trick. Another tactic is abusing REMS programs-FDA safety rules meant to control dangerous drugs. These programs are supposed to protect patients. But some brand companies use them to refuse to sell samples to generic makers. Without those samples, generics can’t prove their product is bioequivalent. No proof? No approval. No approval? No competition. A 2017 study found more than 100 generic companies couldn’t get the samples they needed. One analysis of 40 drugs with restricted access showed this delay cost the system over $5 billion a year. Then there’s disparagement. In the Suboxone case, Reckitt Benckiser told doctors and patients that the original tablet version was unsafe-despite no evidence. They pushed everyone toward their new film version, which they controlled. The FTC called it coercion. The court agreed. They settled for $1.4 billion.Why Courts Are Split

Not every judge sees it the same way. In 2009, a court dismissed a case against AstraZeneca for switching patients from Prilosec to Nexium. Why? Because Prilosec was still on the market. The court said offering a new product was just competition. But in the Namenda case, the court saw the difference: the original drug was gone. That’s the line. If the old version stays, courts tend to say it’s fine. If it’s pulled, they call it anti-competitive. The FTC’s 2022 report noted this inconsistency. Some judges still think generics should just “spend more on advertising” to win back customers. But that ignores reality: once a patient is on a new formulation, they rarely go back.

What’s Being Done

The FTC has been fighting back. After the Namenda ruling, they got a court order forcing Actavis to keep selling the old version for 30 days after generics entered. That gave patients time to switch back. In the Suboxone case, they forced Reckitt to stop spreading false safety claims. The Department of Justice has also stepped in-not just against brand companies, but against generic manufacturers too. In 2023, Teva paid a $225 million fine for price-fixing with other generic makers. Glenmark paid $30 million. This shows regulators are watching both sides. State attorneys general are also acting. New York’s attorney general won an injunction against Actavis in 2014. Other states are following suit.The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about drugs. It’s about trust in the system. Patients expect that when a patent expires, cheaper options become available. When that doesn’t happen, it’s not because of science-it’s because of strategy. The pharmaceutical industry argues that innovation should be rewarded. They say companies shouldn’t be forced to help competitors. But the FTC and courts are starting to see it differently. If a company changes a drug just to avoid competition, and then pulls the old version to lock patients in, that’s not innovation. It’s manipulation. The real winners? Patients who pay less. Insurers who don’t get hit with sky-high bills. Taxpayers who fund Medicare and Medicaid. The losers? Anyone who needs a medication and can’t afford the brand price.What Comes Next

The FTC’s 2022 report was a wake-up call. It didn’t just list problems-it laid out a plan. They’re pushing for clearer laws that define when product hopping crosses the line. They’re urging states to update substitution rules so they cover reformulated drugs. And they’re watching REMS abuse like a hawk. Congress is listening too. In 2023, the House Committee on Appropriations told the FTC to act. Experts predict new legislation could come in the next two years. Until then, the battle continues. Generic companies are getting smarter. Courts are getting more skeptical. And patients? They’re still paying the price.Can pharmacists substitute generics if the brand drug is still available?

Yes, if the original brand drug is still on the market and the pharmacist has the generic version, state substitution laws typically allow the swap. But if the brand company pulls the original version and replaces it with a new formulation, substitution often becomes impossible because the generic version only matches the old drug, not the new one.

What is product hopping and why is it illegal?

Product hopping is when a drug company releases a slightly modified version of a drug near patent expiry and immediately stops selling the original. This blocks pharmacists from substituting cheaper generics because state laws only allow swaps for identical formulations. Courts have ruled this is illegal when the original drug is withdrawn, because it’s not innovation-it’s a tactic to delay competition and keep prices high.

How do REMS programs block generic drugs?

REMS are FDA safety programs meant to manage risks with certain drugs. But some brand companies use them to refuse to sell samples to generic manufacturers. Without those samples, generics can’t run the tests needed to prove their product is safe and effective. No test results? No FDA approval. No approval? No competition.

Has the FTC taken action against these practices?

Yes. The FTC successfully sued Actavis over Namenda, forcing them to keep selling the old version after generics entered. They also settled with Reckitt Benckiser over Suboxone after the company spread false safety claims about the tablet version. The FTC has also pushed for state law changes and published a major report in 2022 detailing these tactics.

Why don’t more generic companies challenge these tactics?

It’s expensive and risky. Lawsuits can take years and cost millions. Many generic makers are small companies with limited resources. Even when they win, the damage is done-patients have already switched, and the brand keeps its market share. That’s why regulatory action from the FTC and DOJ is so important.

What can patients do if they suspect product hopping?

If your pharmacy can’t fill your prescription with a generic and you’re being pushed to a more expensive version, ask your doctor if the original drug is still available. If it’s been pulled, report it to your state pharmacy board or the FTC. Patient pressure can help drive regulatory attention.

12 Comments

Holli Yancey

I never realized how much manipulation goes into something as simple as filling a prescription. It’s scary to think that companies can legally block cheaper options just by changing the pill shape. I’ve seen my dad struggle to afford his meds-this isn’t just corporate greed, it’s a public health crisis.

And honestly, why do we let them get away with it? We’re not talking about life-saving breakthroughs here. We’re talking about tweaking a drug so the generic can’t compete. That’s not innovation. That’s exploitation.

Joseph Peel

The legal inconsistency is staggering. In the Namenda case, the Second Circuit rightly identified the withdrawal of the original formulation as anti-competitive. Yet in AstraZeneca’s Prilosec/Nexium case, the court allowed the same tactic because the original remained on the market. This is not a matter of legal nuance-it is a failure of regulatory coherence. State substitution laws must be amended to encompass reformulated equivalents, regardless of minor delivery mechanism changes.

Kelsey Robertson

Oh, here we go again-the ‘corporate evil’ narrative. Let me guess: next you’ll say Big Pharma is poisoning puppies and bribing dogs? Look, innovation costs money. If companies can’t profit from slightly improved formulations, why would they bother developing anything at all? You want cheaper drugs? Then stop pretending every tweak is ‘fraud.’

Also, generics are cheap because they don’t pay for R&D. That’s not a conspiracy-it’s capitalism. If you don’t like it, move to Sweden and cry into your chamomile tea.

Joseph Townsend

THIS IS A SCAM. A FULL-ON, BLOODY, RED-CLAD, SIREN-SOUNDING SCAM.

They pull the old drug, slap on a new label, and call it ‘innovation’? Please. That’s like a car company making a new color for the same engine and then saying you can’t buy the old model anymore-so you HAVE to pay more. It’s not a business model. It’s a con job dressed in a lab coat.

And don’t even get me started on REMS abuse. That’s like a bouncer at a club refusing to let anyone else in because he’s friends with the VIP. Only the VIP gets in. And guess what? The VIP is the same guy who owns the club. And he’s charging $200 for a beer.

Bill Machi

This is why America is collapsing. We reward failure and punish productivity. These companies are doing exactly what any rational capitalist would do-maximize profit. The problem isn’t the corporations. The problem is the government that lets them play by different rules. Why are we subsidizing drug companies with taxpayer money while they lock out generics? This isn’t capitalism. This is feudalism with IV drips.

And don’t tell me about ‘patients.’ The real patients are the ones who can’t afford insulin. The rest are just whining because their co-pay went from $20 to $50.

Elia DOnald Maluleke

It is a profound tragedy that in the land of the free, the pursuit of profit has eclipsed the pursuit of health. In South Africa, we watch these battles unfold with a mixture of horror and resignation. Our people die because they cannot afford generics that are legally available elsewhere. The pharmaceutical industry, once a beacon of healing, has become a temple of extraction.

When a man in Durban must choose between feeding his children and taking his heart medication, we have lost our moral compass. This is not merely policy failure. It is spiritual decay.

satya pradeep

Bro, this is wild. I work in pharma logistics in India and I’ve seen this firsthand. Companies block samples, delay approvals, and then act shocked when generics don’t launch. Meanwhile, Indian generics are saving millions globally. But here? They get blocked by legal loopholes and REMS abuse. It’s like playing chess with the rules changed mid-game.

And the FTC? They’re trying. But they need more muscle. Congress needs to pass a law that says: if you pull the original, you lose your monopoly rights. Simple. Done.

Prem Hungry

Dear fellow citizens, let us not forget: every dollar saved on generics is a dollar that goes back into a family’s budget-toward food, rent, education. This is not about ‘big pharma’ vs. ‘the little guy.’ This is about dignity. A man should not have to choose between his health and his home. Let us support regulatory reform with the same urgency we give to sports or entertainment.

Let us be the generation that said: enough.

Leslie Douglas-Churchwell

THIS IS ALL A LIE. The FDA, FTC, and Big Pharma are all in cahoots with the Illuminati to control your mind through medication. The ‘generics’ aren’t even real-they’re nano-robots programmed to make you docile. The original drug? That’s the only one that works. They pulled it to force you into the mind-control version. And now they’re using REMS to block the truth.

Also, I saw a tweet that said ‘Suboxone film contains lithium.’ That’s why your teeth are falling out. The government won’t admit it. #PharmaLies #WakeUpSheeple 🧠💊👁️

shubham seth

Let’s cut the BS. The entire system is rigged. These companies don’t care about patients. They care about stock prices. The FTC’s report? A PR stunt. The DOJ fines? A slap on the wrist. Teva paid $225M? That’s pocket change for a company that made $10B last year. They’re laughing all the way to the bank while you’re skipping doses.

And don’t even get me started on how these ‘reformulations’ are barely different. It’s like putting a new sticker on a broken phone and calling it ‘upgraded.’

Kathryn Ware

Reading this made me cry. I’ve worked in community pharmacies for 18 years. I’ve watched elderly patients cry because their $5 generic was suddenly $120 because the brand drug got ‘updated.’ I’ve had to explain to diabetic seniors why they can’t get their old insulin anymore-because the company pulled it and now they have to use a pen they can’t afford.

It’s not just about law or policy. It’s about the human cost. Every time a pharmacist can’t substitute, someone suffers. And we let it happen because we’re too busy scrolling through TikTok to care.

But we can change this. Write to your reps. Support state-level reforms. Demand transparency. This isn’t just about drugs-it’s about who we are as a society. Let’s be better.

kora ortiz

This is why we need real change now. No more loopholes. No more delays. Let generics in. Let patients win.

Write a comment