Understanding How Organ Rejection Leads to Post-Transplant Complications

Transplant Rejection Timeline Estimator

Estimate when complications may develop based on rejection type. This tool helps clinicians and patients recognize early warning signs.

Select Rejection Type

Key Monitoring Indicators

Acute Rejection

Days to weeks post-transplant

Critical markers: Elevated creatinine, fever, graft tenderness

Chronic Rejection

Months to years post-transplant

Critical markers: Progressive functional decline, fibrosis on biopsy

Hyperacute Rejection

Minutes to hours post-transplant

Critical markers: Immediate graft failure, vascular thrombosis

Complication Timeline

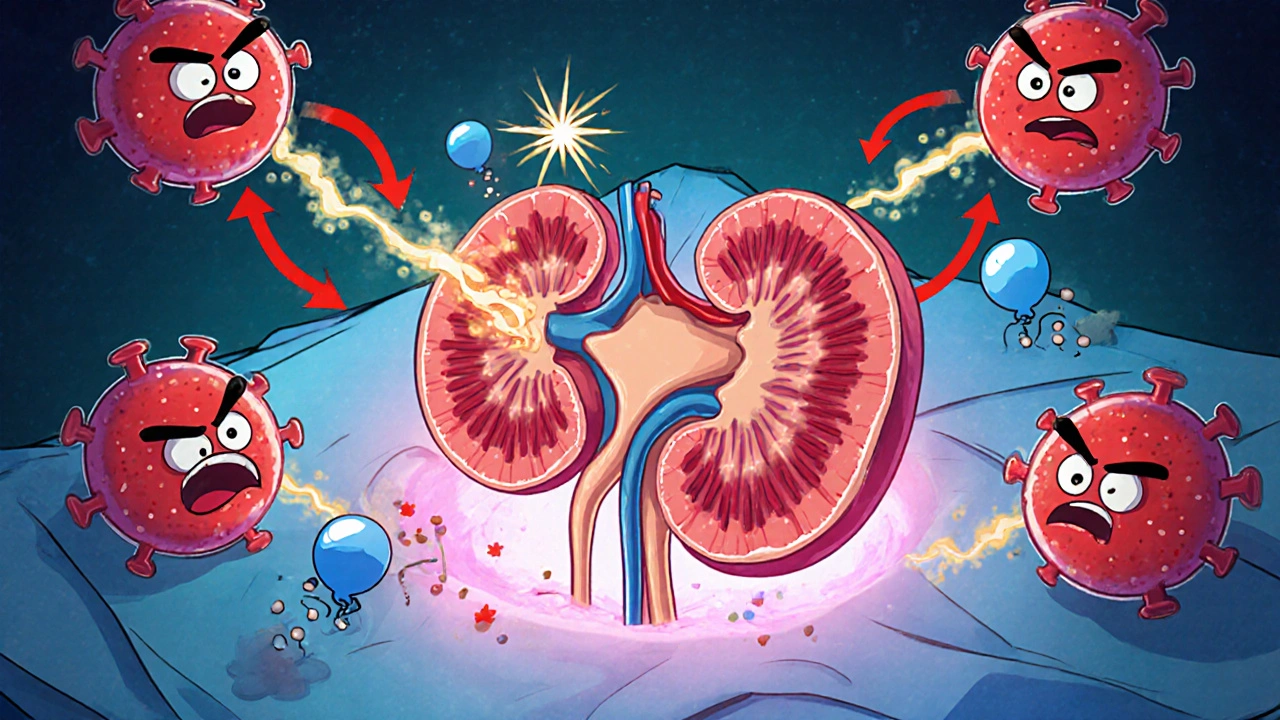

When a new organ is placed inside a recipient, the body’s immune system can see it as a foreign invader. Organ rejection is a complex immune response that can set off a cascade of problems, often showing up as Post‑transplant complications. Understanding that connection helps patients and clinicians act fast, cut down on hospital stays, and protect the graft for the long term.

Why Rejection Triggers Complications

The moment immune cells recognize donor antigens, they release cytokines, recruit more immune players, and damage the blood vessels that supply the graft. This inflammation can directly cause tissue injury, but it also creates the perfect environment for secondary issues like infection, thrombosis, or chronic scarring. In short, organ rejection is the spark; the subsequent complications are the fire that can spread if not contained.

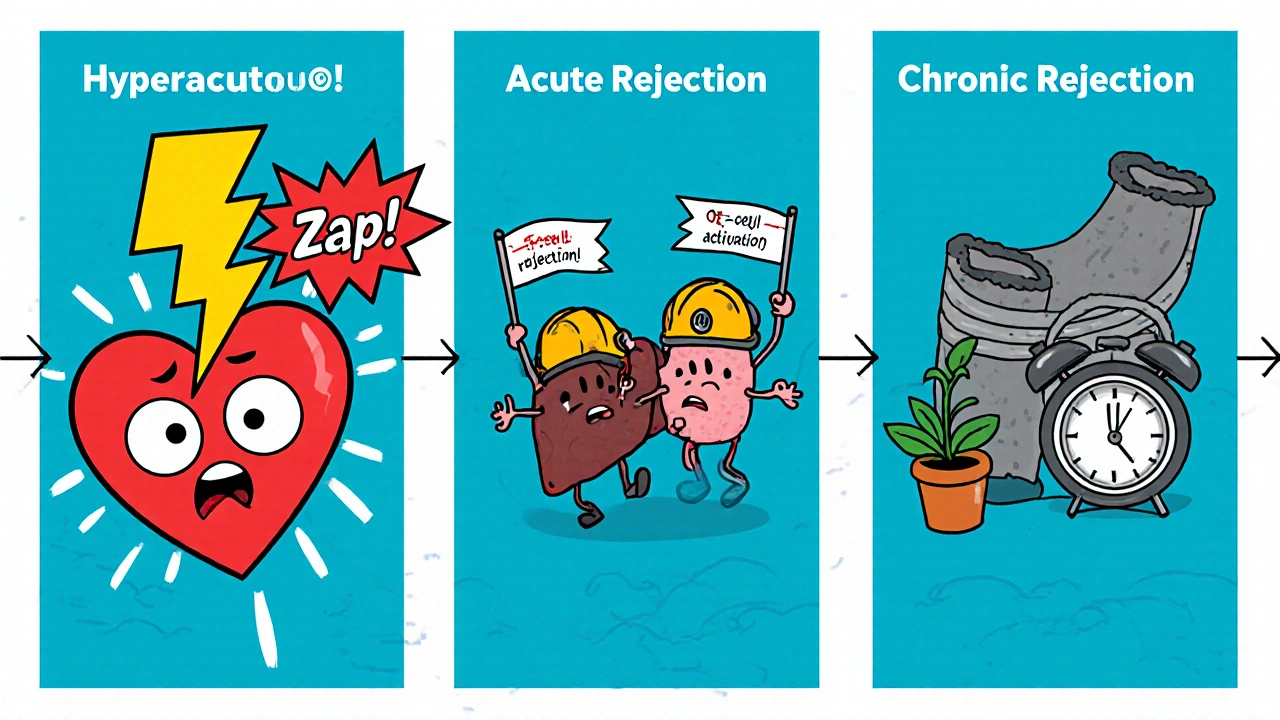

Types of Rejection and Their Timeline

Rejection isn’t a single event. It comes in three main flavors:

- Acute rejection - Happens days to weeks after surgery, driven by T‑cell activation.

- Chronic rejection - Develops months to years later, characterized by vascular narrowing and fibrosis.

- Hyperacute rejection - Rare, occurs within minutes due to pre‑existing antibodies.

Each type brings its own set of risks, but they all share the common thread of immune‑mediated damage that can precipitate other problems.

Key Immunological Pathways

Two pathways dominate the rejection story:

- Cell‑mediated immunity - Cytotoxic T cells recognize donor HLA and kill graft cells.

- Humoral immunity - B cells produce donor‑specific antibodies (DSA) that attack the graft’s vasculature.

When either pathway is active, you often see elevated serum creatinine (in kidney transplants) or rising liver enzymes (in liver transplants), both early warning signs of trouble.

Common Post‑Transplant Complications Linked to Rejection

Below is a quick snapshot of the most frequent complications that either stem directly from rejection or are made worse by it.

| Complication | Typical Onset | Connection to Rejection |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular thrombosis | First few weeks | Endothelial injury from acute rejection promotes clot formation. |

| Infection (CMV, BK virus) | 1-6 months | Intensified immunosuppression to curb rejection leaves patients vulnerable. |

| Chronic allograft dysfunction | 6 months-years | Repeated low‑grade rejection episodes cause fibrosis. |

| Graft‑versus‑host disease (GVHD) | Weeks-months (mostly in bone‑marrow transplants) | Donor immune cells attack host tissues after inadequate rejection control. |

| Ischemia‑reperfusion injury | Immediately post‑surgery | Exacerbated by early immune activation during acute rejection. |

Monitoring and Early Detection Strategies

Timely detection is the game‑changer. Here’s what most transplant centers monitor:

- Routine labs - serum creatinine, liver function tests, complete blood count.

- Immunologic assays - DSA screening, flow cytometry cross‑match.

- Imaging - Doppler ultrasound for vascular flow, MRI for tissue edema.

- Biopsy - The gold standard for confirming acute or chronic rejection.

Combining these tools creates a safety net that catches rejection before it snowballs into a serious complication.

Managing Rejection to Prevent Complications

Once rejection is identified, the treatment plan usually follows two pillars:

- Intensify immunosuppression - High‑dose steroids, anti‑lymphocyte globulin, or newer agents like Tacrolimus and Mycophenolate mofetil are common choices.

- Address secondary risks - Prophylactic antivirals for CMV, anticoagulation for thrombosis, and careful fluid management to reduce ischemic stress.

Balancing enough suppression to stop rejection while avoiding over‑suppression (which fuels infection) is a tightrope walk that requires frequent labs and clinical judgement.

Practical Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

- Know your immunosuppressive regimen - dosage, timing, and side effects.

- Track daily symptoms - fever, pain at the transplant site, changes in urine output or stool color.

- Keep all lab appointments - missing a serum creatinine check can delay detection.

- Report any infections immediately - early treatment reduces the chance of graft injury.

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle - balanced nutrition, moderate exercise, and smoking cessation support graft longevity.

Following this checklist empowers patients to catch warning signs early and gives clinicians a clear roadmap for intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between acute and chronic rejection?

Acute rejection occurs quickly, usually within weeks, and is driven by T‑cell activity that can be reversed with steroids. Chronic rejection develops over months to years, leading to progressive scarring and loss of graft function, and is harder to treat.

How soon after transplant should I expect lab tests?

Most centers run daily labs for the first week, then taper to weekly for the first month, and eventually to monthly checks, depending on stability.

Can infections be a sign of rejection?

Infections themselves are not rejection, but they often appear when immunosuppression is increased to treat rejection, so any new infection should prompt a closer look at graft function.

Is a biopsy always required to confirm rejection?

Biopsy is the definitive test, but clinicians may start treatment based on strong lab and imaging clues while awaiting histology.

What lifestyle changes help prevent complications?

A balanced diet low in sodium, regular low‑impact exercise, avoiding tobacco, and strict adherence to medication schedules all reduce the risk of both rejection and secondary complications.

9 Comments

Drew Waggoner

Seeing the cascade from rejection to complications feels like watching a chain reaction you can’t stop once it starts. The immune system’s fury tears at blood vessels, paving the way for clots and infections. It’s a harsh reminder that the body’s defense can become its own worst enemy. Keeping an eye on those early lab changes is the only way to catch it before the fire spreads.

Mike Hamilton

yeah, i think it really shows how the body can be both protector and destroyer. in simple terms, the first signs are just markers, but they tell a story. sometimes i forget that even a tiny spike in creatinine means a lot more behind the scenes. it’s like a cultural lesson in humility for the immune system.

Matthew Miller

Wow, this whole rejection thing is like a fireworks display gone wrong-bright, explosive, and you better have a fire extinguisher ready! The cytokine storm bursts out, recruiting every soldier in the immune army, and before you know it you’ve got thrombosis, infections, and fibrosis marching in hand‑in‑hand. The drama is real, but the good news is that with the right monitoring toolbox you can douse the flames early. Think of steroid bursts and tacrolimus as your tactical water cannons, while antivirals act like the specialized foam for those nasty viral sparks. Stay sharp, stay proactive, and you’ll keep that graft shining like new.

Linda A

It is curious how the body, in its relentless quest for equilibrium, can turn self‑preservation into self‑destruction. The quiet acceptance of this paradox may guide us toward more compassionate care.

Joe Moore

theyre all in on a secret agenda to make us sick.

Ayla Stewart

The interplay between immunosuppression and infection risk is a delicate balance that clinicians must navigate constantly.

Poornima Ganesan

First, it is essential to acknowledge that rejection is not a singular event but a spectrum of immune-mediated assaults that can manifest at any time post‑transplant. Acute rejection, with its rapid T‑cell activation, often serves as the initial spark, while chronic rejection, driven by persistent low‑grade inflammation, quietly builds a fibrotic wall around the graft over months and years. Hyperacute rejection, though rare, illustrates the dire consequences of pre‑existing antibodies that act like a pre‑loaded cannon, obliterating the organ within minutes. Each of these pathways, despite their temporal differences, converges on a common endpoint: endothelial injury. When the endothelial lining is compromised, it not only facilitates thrombosis but also serves as a gateway for opportunistic pathogens, creating a perfect storm for infection. Moreover, the very act of intensifying immunosuppression to combat rejection paradoxically amplifies the vulnerability to viruses such as CMV and BK, as well as bacterial sepsis. This duality underscores the tightrope clinicians walk when calibrating drug regimens. Diagnostic vigilance, therefore, must extend beyond routine labs; imaging modalities like Doppler ultrasound and MRI provide real‑time insights into vascular integrity, while tissue biopsies remain the gold standard for histological confirmation. The integration of serological markers, such as donor‑specific antibodies, with functional imaging creates a multi‑layered safety net that can catch early signs of rejection before they cascade into irreversible damage. Therapeutically, the use of high‑dose steroids, anti‑lymphocyte globulin, and newer agents such as tacrolimus must be balanced with prophylactic antivirals and anticoagulation strategies to mitigate secondary complications. Patient education plays a pivotal role as well; self‑monitoring for subtle changes in urine output, fever, or wound appearance can accelerate clinical intervention. In sum, understanding the intertwined nature of rejection and its downstream complications equips both clinicians and patients with the foresight needed to preserve graft function over the long term.

Emma Williams

Absolutely, the comprehensive approach you outlined makes a lot of sense.

Albert Fernàndez Chacón

Totally agree with the previous point; keeping the immunosuppressive cocktail balanced is like fine‑tuning a complex system, and the jargon around DSA screening or flow cytometry really helps us speak the same language when we talk about early detection.

Write a comment