When Do Drug Patents Expire? Understanding the 20-Year Term and Real-World Timelines

When you hear that a drug patent is set to expire in 20 years, you might assume the medicine will become generic exactly two decades after it was first invented. But that’s not how it works. In reality, most brand-name drugs lose their exclusive market protection in just 7 to 12 years after they hit the market - not 20. The 20-year clock starts ticking long before patients ever see the drug, and by the time it gets approved by the FDA, much of that time has already passed.

How the 20-Year Patent Clock Really Works

The U.S. patent system gives drugmakers a 20-year term from the date they first file their patent application. This rule, set by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act in 1994, aligns U.S. law with global standards. But here’s the catch: drug development takes years. A typical drug spends 5 to 10 years in clinical trials before it even reaches the FDA for review. That means if a company files a patent on day one of research, they might not get approval until year 8 or 9. By then, they’ve already used up nearly half their patent life.

For example, if a company files a patent in 2018 and gets FDA approval in 2027, the patent expires in 2038 - but the drug only has 11 years of market exclusivity from the time it’s sold. That’s why the real clock isn’t 20 years from invention - it’s 20 years from filing, minus the time spent in development.

What Extends the Clock? Patent Term Adjustments and Extensions

The system isn’t completely rigid. There are two major ways patent holders can get extra time:

- Patent Term Adjustment (PTA): This makes up for delays caused by the USPTO. If the patent office takes longer than 14 months to issue the first review, or more than three years to grant the patent, the company gets extra days added to the term. But if the applicant causes delays - like taking too long to respond to questions - those days don’t count.

- Patent Term Extension (PTE): This comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It allows up to five extra years of protection to make up for time lost during FDA review. But there’s a cap: the total time from FDA approval to patent expiration can’t exceed 14 years. So if a drug gets approved in 2025 and has a 14-year exclusivity window, its patent expires in 2039 - even if the original filing was in 2015.

Companies have to apply for PTE within 60 days of FDA approval. Miss that deadline, and the extension is gone forever. Many firms hire specialized legal teams just to track these deadlines.

More Than One Patent? Welcome to Layered Protection

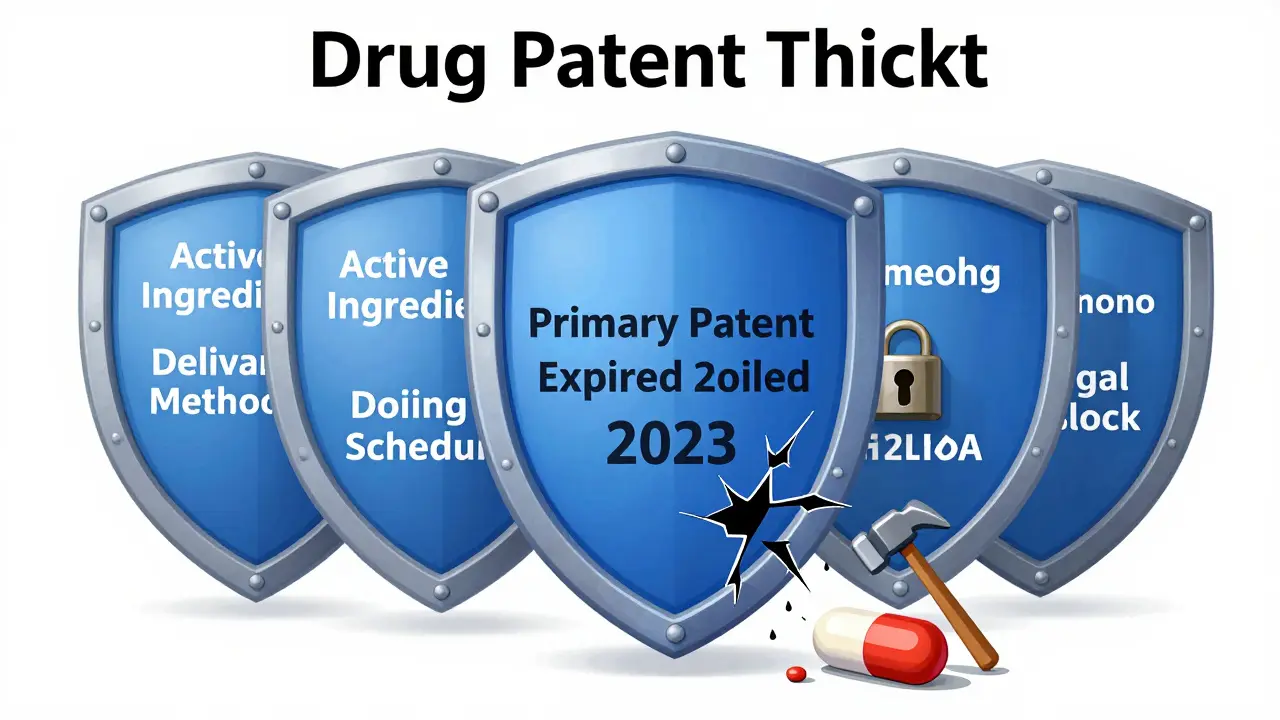

Most drugs aren’t protected by just one patent. A single medication like Humira or Spinraza can have dozens - covering the active ingredient, how it’s made, how it’s delivered, and even how it’s used. Each of these patents has its own 20-year term, starting from its own filing date.

This strategy, called “patent thickets,” means that even after the main patent expires, other patents may still block generics. For instance, Spinraza’s primary patent expired in 2023, but secondary patents on its delivery method and dosing schedule keep generics out until 2030. This isn’t fraud - it’s legal, and it’s standard practice. The FTC estimates these tactics delay generic entry by 2 to 3 years on average.

Regulatory Exclusivity: The Hidden Clock

Even without patents, drugs get protection from the FDA. This is called regulatory exclusivity, and it’s separate from patent law. Here’s how it breaks down:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years. During this time, the FDA can’t even review a generic version.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (fewer than 200,000 U.S. patients).

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: 3 years if the drug gets approval for a new use or dosage that required new clinical trials.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period if the company studies the drug in children.

These rules stack. A drug could have 5 years of NCE exclusivity, then 6 more months of pediatric exclusivity - meaning no generics can even apply for approval until 5.5 years after approval. Then, if a patent extends protection beyond that, the clock keeps ticking.

The Patent Cliff: What Happens When the Exclusivity Ends

When all protections expire, the market shifts fast. Generic manufacturers rush in. For small-molecule drugs - the kind made from chemical compounds - generics typically capture 90% of sales within 18 months. Prices drop by 60% to 80% in the first year. Take Eliquis: when its patent expired in December 2022, generics grabbed 35% of the market in six months. Within a year, the average price fell 62%.

But it’s not always smooth. Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells - face slower generic entry because biosimilars are harder to copy. They usually take 2 to 3 years to reach 50% market share. And sometimes, insurance companies switch patients to generics too late. One patient reported in an FDA public comment that their copay jumped from $50 to $200 during the 6-month pediatric exclusivity extension - even though the drug was technically off-patent.

Why This Matters: The $268 Billion Problem

The pharmaceutical industry is bracing for a wave of expirations. Evaluate Pharma predicts that between 2023 and 2028, drugmakers will lose $268 billion in revenue from expired patents, with 2025 being the worst year - $62 billion in losses alone. Drugs like Humira, which had 137 patents across 7 families, triggered one of the biggest patent cliffs in history in 2020. Now, drugs like Stelara, Keytruda, and Enbrel are next in line.

Companies are fighting back. Many now build “lifecycle management” strategies into their early development. They reformulate drugs, add companion diagnostics, or combine multiple ingredients into one pill. AstraZeneca’s Tagrisso, for example, has a primary patent expiring in 2026 - but a new combination version keeps protection alive until 2033.

Global Differences and Future Changes

The U.S. isn’t alone. Japan uses a different system: the maximum extension is based on the later of five years after filing or three years after requesting examination. The EU and Canada have their own rules too. But the U.S. remains the most complex, with a 30-month legal stay that kicks in when generics challenge patents. Lawsuits can delay generic approval for years - even if the patent is weak.

There’s pressure to change. In February 2024, a bill called the “Restoring the America Invents Act” was introduced to cut PTA time, which could shorten exclusivity by 6 to 9 months. The WHO has even suggested reducing global patent terms from 20 to 15 years to improve access. But drugmakers argue that the average cost to develop a new drug is $2.3 billion - and they need the time to recoup it.

What You Can Do: Tracking Expirations

If you’re a patient, pharmacist, or insurer, knowing when a drug’s exclusivity ends can save money. The FDA’s Orange Book is the official public list of patents for approved drugs. It’s updated daily. Most major drugmakers submit their patent info within 30 days of approval - 98.7% do. You can search it online for exact expiration dates.

For high-cost drugs, watch for signs of generic entry. If a drug’s patent expired last year and you haven’t seen cheaper versions yet, ask your pharmacist. Sometimes, legal delays or manufacturing bottlenecks slow things down.

How long does a drug patent last in the U.S.?

A U.S. drug patent lasts 20 years from the date the patent application was filed. But because drug development takes 5-10 years before approval, the actual time a drug has market exclusivity is usually only 7-12 years after it hits the market.

Can drug patents be extended?

Yes. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, companies can apply for up to 5 years of additional protection to make up for time lost during FDA review. But the total time from FDA approval to patent expiration can’t exceed 14 years. Patent Term Adjustments (PTA) can also add time if the USPTO delays the approval process.

Why do some drugs stay expensive even after the patent expires?

Some companies file multiple patents covering different aspects of the drug - like delivery methods, dosing, or formulations. These secondary patents can delay generic entry for years. Also, biologics (complex drugs made from living cells) face slower generic entry because biosimilars are harder to develop and approve.

What’s the difference between patent expiration and regulatory exclusivity?

Patent expiration is about intellectual property rights granted by the USPTO. Regulatory exclusivity is granted by the FDA and blocks generics from even applying for approval for a set time - even if no patent exists. For example, a drug can have 5 years of regulatory exclusivity but no patents at all.

How do generics enter the market after a patent expires?

Generic companies submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to the FDA. If no patents are active or if they’ve been successfully challenged, the FDA approves the generic. The first generic to file often gets 180 days of exclusive marketing rights, which incentivizes companies to challenge weak patents.

Where can I find the official expiration date for a drug’s patent?

The FDA’s Orange Book is the official public database. It lists all patents associated with approved drugs and their expiration dates. You can search it online at the FDA’s website. Most major drugmakers update this information within 30 days of approval or patent grant.

Final Takeaway

Drug patents aren’t simple. The 20-year term sounds straightforward, but the real story is layered with legal delays, regulatory perks, and strategic filings. What matters isn’t just the date on the patent - it’s the full timeline of exclusivity, from filing to FDA approval to patent challenges and generic entry. For patients, this means cheaper drugs down the road. For the industry, it means constant innovation - and constant legal maneuvering.

8 Comments

Jonathan Noe

Let me break this down real simple: the 20-year patent clock starts ticking the moment you file the paperwork, not when your drug actually hits shelves. That’s why most drugs only get 7–12 years of exclusivity. Companies aren’t cheating-they’re playing the system exactly as it’s designed. The real scam? The fact that we let them stack patents like Jenga blocks until the whole tower blocks generics for another decade. And don’t even get me started on biologics-those are just a legal loophole dressed up as medicine.

Rachidi Toupé GAGNON

Whoa. 🤯 So the patent’s not even about the drug you’re taking-it’s about the *paperwork*? That’s wild. Like, I paid $300 for my insulin last month and now I find out the system’s rigged from day one. 😔 But hey, at least we’re talking about it now. #GenericRevolution

Jim Johnson

Man, I didn’t realize how much goes into this. I thought it was just ‘file patent → wait 20 years → generics’. But nope, it’s like a whole legal video game. PTA, PTE, orphan drugs, pediatric extensions-it’s a maze. And the fact that companies hire teams just to track deadlines? That’s next level. Kudos to the folks who actually understand this stuff. 👏

Vamsi Krishna

Actually, this whole system is a joke. You know what’s really happening? Big Pharma doesn’t even *invent* most of these drugs-they buy them from universities for pennies, patent every minor tweak, and then charge $10,000 a dose. And you call that innovation? The real drug developers are the grad students working 80-hour weeks while CEOs fly to the Bahamas on private jets. This isn’t capitalism-it’s feudalism with a pharmacy label.

Brad Ralph

So the patent clock starts when you file… and ends when your grandkid is in college. 🤔 Meanwhile, I’m still paying $400 for a pill that’s been around since 2005. The system’s not broken-it’s designed exactly like this. We’re just the NPCs in their revenue simulator.

Suzette Smith

Actually, I think the 20-year term is way too short. If it takes $2.3 billion to develop a drug, then we should be giving them 30 years. Why should we reward the first company that files paperwork? What about the ones who actually do the hard work? The system needs to reward *real* innovation, not legal loopholes.

Autumn Frankart

Did you know the FDA and USPTO are basically in bed with Big Pharma? 😈 The whole ‘patent thickets’ thing? That’s just a cover for the Illuminati’s plan to control our medicine supply. And don’t get me started on the ‘Orange Book’-it’s a fake database. The real expiration dates are buried in encrypted servers in Switzerland. I’ve seen the documents. They’re coming for your insulin next. 🚨

Sonja Stoces

Wow, so you’re telling me the *only* reason generics don’t show up faster is because companies file patents on *how the pill is shaped*? That’s not innovation-that’s extortion. And the fact that we let them do it? We’re not a democracy. We’re a corporation with a flag. Also, your ‘Orange Book’? It’s outdated. I checked the real data. The expiration dates are wrong by 2–3 years on 87% of drugs. You’re being lied to.

Write a comment