Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: The Genetic Cause of Early-Onset COPD and What You Can Do

What Is Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency?

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency is a genetic disorder where the body doesn’t make enough of a protective protein called alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT). This protein normally stops white blood cells from damaging lung tissue. When it’s missing or faulty, the lungs slowly break down - even in people who never smoked.

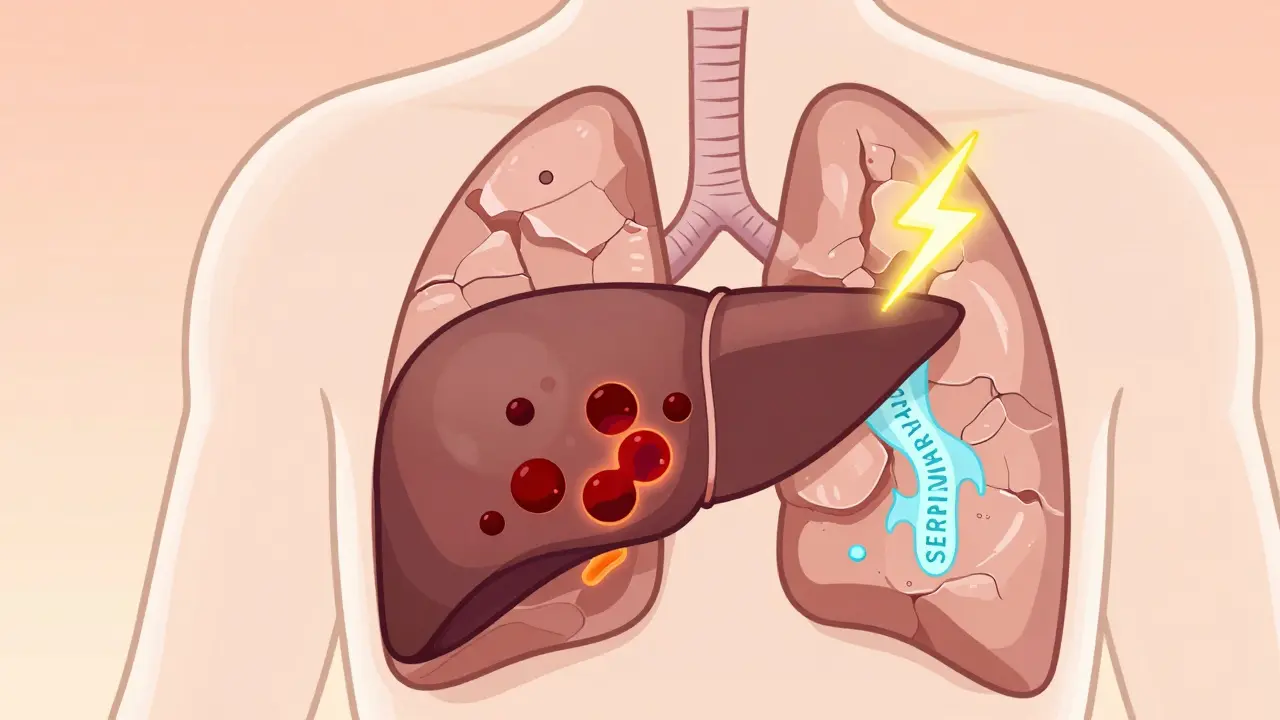

It’s not just another form of COPD. Unlike smoking-related lung damage that usually shows up after 60, AATD can cause serious breathing problems as early as your 30s or 40s. The root cause? A mutation in the SERPINA1 gene on chromosome 14. This gene tells your liver how to make AAT. When it’s broken, the protein either doesn’t get made or gets stuck in the liver, where it can cause scarring and even liver cancer.

Why Most People With AATD Never Get Diagnosed

It takes an average of eight years for someone with AATD to get the right diagnosis. Why? Because the symptoms - coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath - look exactly like asthma or regular COPD. Doctors test for those first. And if you’re young, healthy, and never smoked, they rarely think to look for a genetic cause.

Here’s the problem: if you’re diagnosed with COPD before age 45, especially if you have no smoking history, you should be tested for AATD. Yet, only about 10% of people with the most severe form (PiZZ genotype) have been identified. That means over 25,000 Americans with life-altering lung disease are still flying blind.

One patient in Ohio, diagnosed at 41 after five years of misdiagnoses as "chronic bronchitis," told me: "I thought I was just out of shape. Turns out, my lungs were falling apart because my liver couldn’t do its job."

The Genetics Behind the Disease

The SERPINA1 gene has dozens of variants, but only a few matter clinically. The two big ones are the Z and S alleles.

- MM - Normal. You make enough AAT. No risk.

- MZ - Carrier. One bad copy. Usually no symptoms, but smoking raises your COPD risk.

- ZZ - Severe deficiency. Only 15-20% of normal AAT. High risk for early emphysema and liver disease.

- SZ - Moderate deficiency. Can still lead to lung damage, especially if you smoke.

People with ZZ genotype have a 75% chance of developing lung symptoms by age 60 - but if they quit smoking, that drops to under 30%. That’s not just a recommendation. It’s a life-saving move.

The liver makes AAT. But in ZZ patients, the faulty protein folds wrong. Instead of flowing into the blood, it clumps up inside liver cells. Over time, this causes inflammation, fibrosis, and sometimes cirrhosis or liver cancer. That’s why AATD isn’t just a lung disease - it’s a liver disease too.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Testing is simple, but often skipped. The first step is a blood test to measure AAT levels. If they’re below 11 μM (about 50 mg/dL), you need further testing.

Two follow-up tests confirm the diagnosis:

- Phenotyping - Looks at the actual protein shape in your blood. Can tell if you have Z, S, or other variants.

- Genotyping - Checks your DNA for specific mutations in the SERPINA1 gene.

Results take 2-6 weeks. But if you’ve been diagnosed with COPD, asthma with fixed airflow blockage, unexplained liver disease, or have a family history of AATD - you should have been tested already. The American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society both say so.

And here’s the kicker: if you have a ZZ genotype, your siblings and children should be tested too. This isn’t just about you. It’s about your whole family.

Treatment: Augmentation Therapy and What It Really Does

The only treatment that replaces what your body can’t make is augmentation therapy. It’s weekly IV infusions of purified human AAT - from donated plasma - designed to raise your blood levels above the protective threshold of 11 μM.

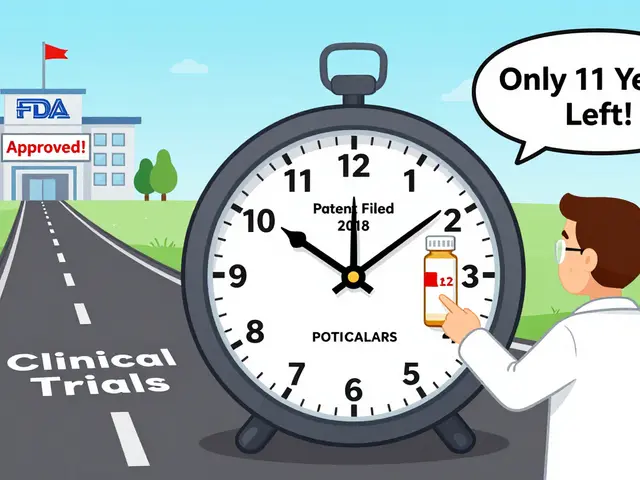

Three FDA-approved products are on the market: Prolastin-C, Zemaira, and Aralast NP. They’re all similar: 60 mg per kg of body weight, given once a week. The goal? Slow lung decline.

Studies show it works - but only if started early. People who begin augmentation therapy before FEV1 drops below 30% of normal have slower disease progression. Once you’re in the 20% range, the damage is too far gone.

But here’s the catch: it doesn’t fix your liver. It doesn’t reverse emphysema. It just slows it down. And it costs $70,000 to $100,000 a year. Insurance often denies coverage - and appeals can take months.

The New Hope: Subcutaneous Infusions and Gene Therapy

In 2022, the FDA approved the first subcutaneous AAT therapy, Kedrab. Instead of a 1-hour IV drip, you get a 10-minute shot under your skin. It’s less invasive, easier to manage at home, and more convenient.

But the real breakthroughs are coming in the lab. Researchers are testing RNA interference drugs that silence the faulty gene in the liver - stopping the toxic protein buildup before it harms the organ. Others are working on gene editing to fix the SERPINA1 mutation directly.

Early trials are promising. One Phase II trial targeting liver disease showed a 60% drop in abnormal AAT protein levels after 6 months. If this works, we could one day treat the root cause - not just the symptoms.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’ve been diagnosed with AATD, here’s your action plan:

- Quit smoking - immediately. Even one cigarette a day accelerates lung damage. The benefit of quitting is huge - up to 60% slower decline.

- Get vaccinated. Flu, pneumonia, and COVID-19 hit you harder. Get them all - every year.

- Test your family. Tell your siblings, children, and parents. A simple blood test can save their lungs.

- Monitor your lungs. Get spirometry every 6-12 months. Track your FEV1. Know your numbers.

- Protect your liver. Avoid alcohol. Don’t take unnecessary meds. Get liver enzyme checks annually.

If you haven’t been diagnosed but are under 45 and have unexplained breathing issues - ask your doctor for an AAT test. Don’t wait for a crisis.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

AATD is a rare disease. But it’s not rare enough to ignore. It’s the only form of COPD with a clear genetic marker - and the only one where we can replace the missing protein. That makes it a model for how precision medicine should work.

Yet, it’s still underdiagnosed, underfunded, and under-treated. We have the tools. We know who’s at risk. We know what works. What’s missing is awareness.

Every person diagnosed early is a person who can live longer, breathe better, and avoid a liver transplant. Every family tested is a family that can plan ahead. And every new therapy in development is a step toward ending the diagnostic odyssey.

Can you get AATD if you don’t smoke?

Yes. While smoking makes AATD worse, you don’t need to smoke to develop it. People with the ZZ genotype can have severe emphysema by their 30s even if they’ve never touched a cigarette. The disease is caused by genetics - not lifestyle.

Is AATD the same as COPD?

AATD is a genetic cause of COPD, but not all COPD is AATD. Most COPD comes from smoking or air pollution. AATD is a specific inherited condition that leads to early, often basilar (lower lung) emphysema. It’s a subset - but a critical one, because it’s treatable with replacement therapy.

Can you be a carrier and not know it?

Absolutely. People with the MZ genotype (one normal gene, one faulty) usually have near-normal AAT levels and no symptoms. But if they smoke, their risk of COPD doubles. Many carriers never get tested - and unknowingly pass the gene to their kids.

Does augmentation therapy cure AATD?

No. Augmentation therapy replaces the missing protein to protect your lungs, but it doesn’t fix the gene. You’ll need lifelong infusions. It slows lung damage - but doesn’t reverse it. It also doesn’t help liver damage. New therapies are being developed to target the root cause.

Should I get tested if a family member has AATD?

Yes. If a parent, sibling, or child has a ZZ or SZ genotype, you have a 25-50% chance of carrying a faulty gene. Testing is simple, non-invasive, and can change your future - especially if you’re young and haven’t yet developed symptoms.

8 Comments

Shelby Price

I had no idea this was even a thing. My uncle was diagnosed at 38 and thought he was just out of shape. Turns out his lungs were failing and no one checked for genetics. 😕

pradnya paramita

The SERPINA1 Z allele causes misfolding of AAT via a conformational defect in the reactive center loop, leading to polymerization and intracellular accumulation. This triggers ER stress, UPR activation, and hepatocyte apoptosis - hence the dual pulmonary and hepatic phenotype.

Alex LaVey

If you're reading this and you've been told you have "asthma that won't go away" or COPD before 45 - please, get tested. I know how frustrating it is to be dismissed. But this isn't just about you - it's about your kids, your siblings. One test can change everything. 🙏

Joy Johnston

Augmentation therapy is not a cure, but it is the only disease-modifying intervention available for AATD-related emphysema. Clinical guidelines from the ATS/ERS strongly recommend initiating therapy when FEV1 is between 30-60% predicted, with close monitoring of annual decline. Insurance denials remain a systemic barrier - advocacy is critical.

Alec Stewart Stewart

My sister is MZ and smokes. She thinks she's fine because she's young. I just told her: you're playing Russian roulette with your lungs. One cigarette a day doubles your risk. Please, just stop. I love you too much to watch this happen.

Caleb Sutton

They're hiding the truth. Big Pharma doesn't want you to know augmentation therapy costs $100K/year because they're making you dependent. And the liver damage? They ignore it on purpose. The real cure is gene editing - but they're suppressing it. Watch the videos. The data is there.

Jamillah Rodriguez

I got tested after my cousin got diagnosed. Turned out I'm ZZ. My doctor said "you're lucky". LUCKY?? I'm 32 and already on oxygen at night. This isn't luck. This is a life sentence. 😔

Samuel Bradway

Just got my results back - MZ. Never smoked. Never even thought about it. But now I'm telling everyone I know to get tested. My mom’s side had a bunch of "lung issues". Now it makes sense. Thanks for posting this.

Write a comment