Managing Warfarin and Antibiotics: Common Interaction Issues

Warfarin-Antibiotic Interaction Checker

Check Antibiotic Interaction Risk

Select your antibiotic and warfarin dose to see potential interaction risk

Interaction Results

When you're on warfarin, even a simple course of antibiotics can throw your blood thinner off balance - and not in a minor way. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happened to real people: a 72-year-old man in Oxford goes in for a tooth extraction, gets prescribed amoxicillin, and three days later ends up in the ER with a subdural hematoma because his INR spiked to 8.2. Or a woman on warfarin for atrial fibrillation takes cotrimoxazole for a UTI and bleeds internally from a minor fall. These aren’t rare cases. They’re predictable - and preventable.

Why Antibiotics and Warfarin Don’t Play Nice

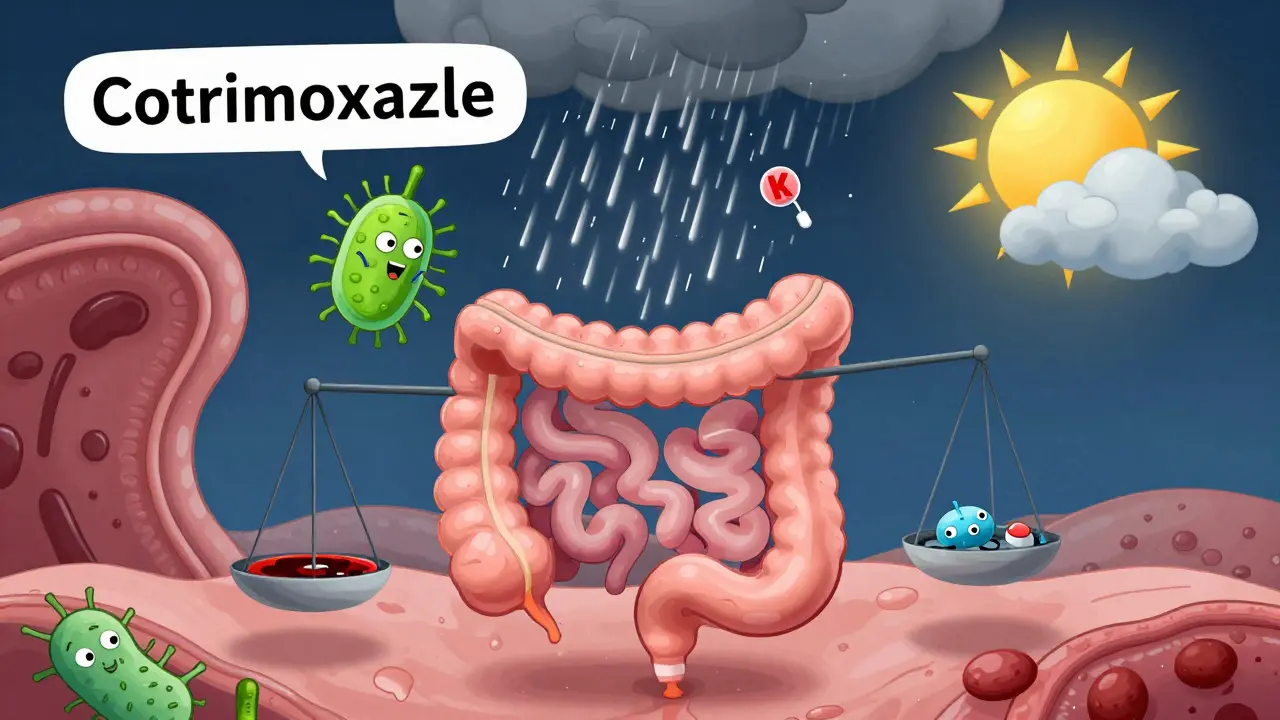

Warfarin works by blocking vitamin K, which your body needs to make clotting factors. It’s a tightrope walk: too little, and you risk clots; too much, and you bleed. The therapeutic window is narrow - INR between 2.0 and 3.0 for most people. Now add antibiotics into the mix, and that balance gets disrupted in three different ways.First, some antibiotics shut down the liver enzyme CYP2C9, which breaks down warfarin. When this enzyme slows down, warfarin builds up in your blood. That’s why drugs like cotrimoxazole (Bactrim), ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin can cause INR to jump 1.5 to 3 points within days. Cotrimoxazole is especially dangerous - it doesn’t just inhibit the enzyme, it also kills off gut bacteria that make vitamin K, and it displaces warfarin from protein binding sites. It’s a triple threat.

Second, broad-spectrum antibiotics wipe out the friendly bacteria in your intestines. These bugs produce about 10-15% of your daily vitamin K. When they’re gone, your body can’t make enough clotting factors, even if you’re taking the same warfarin dose. That’s why even antibiotics like ceftriaxone - which don’t touch liver enzymes - can still spike INR. It’s not about the drug itself; it’s about what it kills in your gut.

Third, there’s the flip side: rifampin. This antibiotic does the opposite. It cranks up CYP2C9 activity by 300-400%. That means warfarin gets broken down too fast. Your INR drops. You’re at risk of stroke or pulmonary embolism. And here’s the kicker - it doesn’t happen right away. It takes 1-2 weeks for rifampin to fully induce the enzyme. So you might feel fine for days, then suddenly your INR crashes.

Which Antibiotics Are High Risk?

Not all antibiotics are created equal when it comes to warfarin. Some barely move the needle. Others are red flags.High-risk antibiotics (INR increase >1.5 units in over 30% of patients):

- Cotrimoxazole (Bactrim, Septra) - highest risk. Often requires a 50% warfarin dose reduction.

- Fluconazole - an antifungal, but commonly prescribed. Strong CYP2C9 inhibitor.

- Metronidazole - used for anaerobic infections, dental abscesses. Potent inhibitor.

Moderate-risk antibiotics (INR increase 0.5-1.5 units in 20-30% of patients):

- Fluoroquinolones - ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin. Common for UTIs and respiratory infections.

- Macrolides - erythromycin, clarithromycin. Used for pneumonia, sinusitis.

- Penicillins - amoxicillin, ampicillin. Often prescribed for dental work or strep throat.

- Cephalosporins - ceftriaxone, cephalexin. Especially ceftriaxone, which affects gut flora more than liver enzymes.

Low-risk antibiotics (INR increase <0.5 units, rarely clinically significant):

- Clindamycin - minimal interaction. Often recommended for dental prophylaxis in warfarin patients.

- Azithromycin - weak CYP2C9 inhibition. Safer than erythromycin.

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate - slightly higher risk than plain amoxicillin, but still manageable.

And then there’s rifampin - the exception that breaks the rule. It doesn’t raise INR. It crashes it. You’ll need to increase your warfarin dose by 50-100% - but not right away. Wait 7-10 days, then adjust based on INR trends. Don’t rush it. It takes 6-8 weeks for the enzyme induction to stabilize.

What You Should Do When Starting an Antibiotic

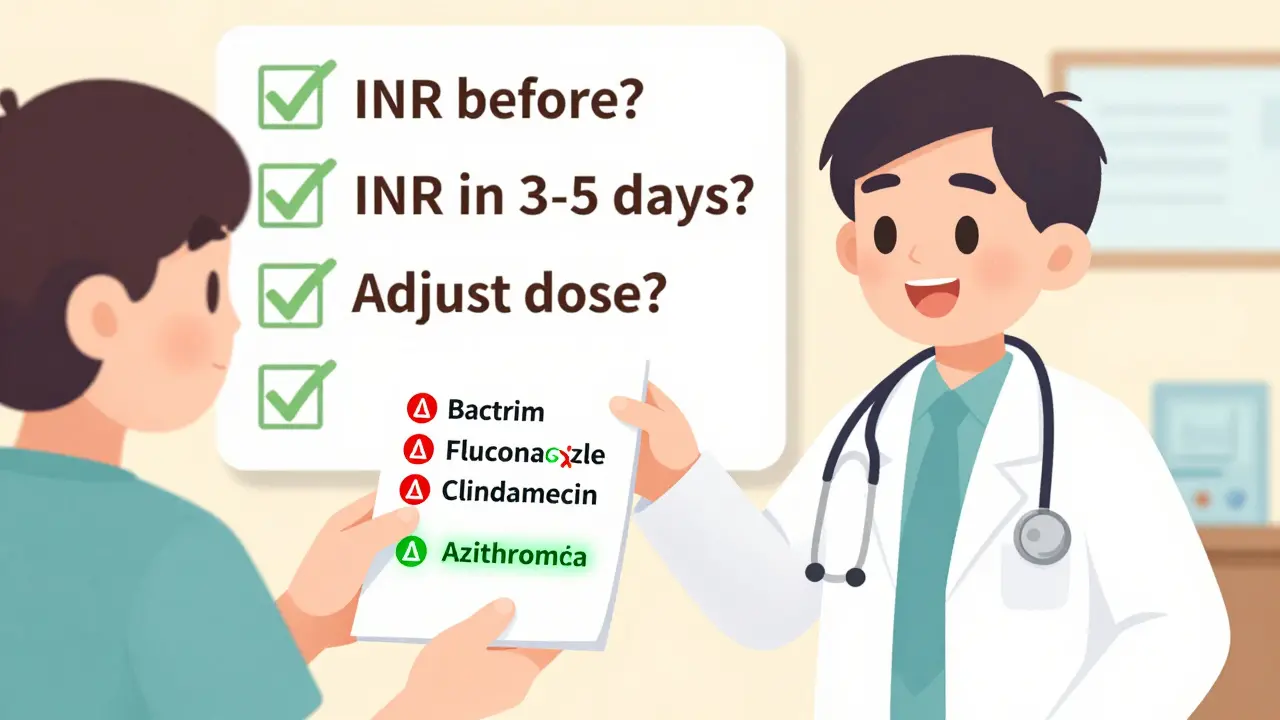

If you’re on warfarin and your doctor prescribes an antibiotic, don’t panic. But don’t assume everything’s fine either. Here’s what actually works:- Check your INR before starting the antibiotic. Get a baseline. This isn’t optional. If your INR is already 2.8 and you’re about to take Bactrim, you’re already close to danger.

- Check again in 3-5 days. For high-risk antibiotics like cotrimoxazole or fluconazole, test at day 3. For moderate ones like ciprofloxacin or amoxicillin, day 5 is fine. Don’t wait until your next scheduled check-up.

- Adjust warfarin dose based on the result. If INR jumped 1.5 points, reduce your weekly dose by 25-50%. If it’s only up 0.8, reduce by 10-15%. Don’t guess. Use your clinic’s protocol. If you’re unsure, call your anticoagulation clinic.

- For rifampin, expect to increase your dose. Start checking INR every 3-4 days after day 5. You’ll likely need to increase your warfarin dose gradually over 2-3 weeks.

- Watch for signs of bleeding. Unexplained bruising, nosebleeds that won’t stop, dark stools, headaches, or dizziness. Don’t wait for INR results if you’re bleeding.

And here’s something most patients don’t realize: you don’t always need to stop warfarin. In fact, stopping it increases your risk of clotting more than the antibiotic increases your risk of bleeding. The goal is to adjust, not abandon.

What About Dental Work?

A lot of warfarin patients get nervous about dental cleanings or extractions. The old advice was to stop warfarin. That’s outdated. The American Heart Association says: keep taking it. The risk of a clot from stopping warfarin is higher than the risk of bleeding from a tooth extraction.For antibiotics, though - if you need prophylaxis (prevention) before dental work, clindamycin is the go-to. It has the lowest interaction risk. Avoid amoxicillin if you can. If your dentist insists on amoxicillin, get your INR checked the day before and again 3 days after. That’s all it takes.

One study from 2003 followed 142 warfarin patients who had dental extractions. Only two had INRs over 4.0. Neither had serious bleeding. The key? They checked INR after the procedure. Not before. Not after the fact - after.

Why This Keeps Happening

You’d think, after 70 years of warfarin use, doctors would know this. But here’s the problem: most antibiotic prescriptions are written by general practitioners, not cardiologists or anticoagulation specialists. And most GPs don’t think about warfarin unless you tell them.Patients don’t always volunteer that they’re on blood thinners. They say, “I’m on a heart pill,” or “I take something for my blood.” They don’t say “warfarin.” They don’t know the name. They don’t realize it’s dangerous.

And even when they do, the guidance is inconsistent. Some clinics say “reduce dose by 25%.” Others say “hold one dose.” There’s no universal rule. That’s why the University of Michigan and UC San Diego have published detailed protocols - because the stakes are too high to wing it.

The Bottom Line

Warfarin and antibiotics can coexist safely - but only if you treat the interaction like a live wire. Don’t ignore it. Don’t overreact. Just monitor.Every time you start a new antibiotic, ask yourself:

- Is this a high-risk drug? (Bactrim? Fluconazole? Metronidazole?)

- Did I get my INR checked before starting?

- Will I check it again in 3-5 days?

- Do I know what to do if it’s up?

If you can answer yes to all four, you’re doing better than most. Most people don’t even know these questions exist.

The truth is, you don’t need to avoid antibiotics. You need to manage the interaction. And that’s not hard - if you’re prepared.

Can I take amoxicillin while on warfarin?

Yes, you can take amoxicillin while on warfarin, but it’s not risk-free. Amoxicillin is considered a moderate-risk antibiotic. It can raise your INR by 0.5 to 1.5 units in about 20-30% of people, mostly due to gut bacteria disruption. Check your INR before starting the antibiotic, then again 5-7 days after. You may need to reduce your warfarin dose by 10-25%. Don’t stop either medication unless your doctor tells you to.

What’s the most dangerous antibiotic to take with warfarin?

Cotrimoxazole (Bactrim or Septra) is the most dangerous. It’s a triple threat: it inhibits the CYP2C9 enzyme that breaks down warfarin, kills vitamin K-producing gut bacteria, and displaces warfarin from protein binding sites. Studies show it increases the risk of major bleeding by over three times compared to other antibiotics. If you’re on warfarin and need an antibiotic, avoid Bactrim unless absolutely necessary. If you must take it, expect to reduce your warfarin dose by 50% and check your INR within 72 hours.

Do I need to stop warfarin before taking antibiotics?

No, you should not stop warfarin. Stopping it increases your risk of stroke, heart attack, or pulmonary embolism - which is far more dangerous than the bleeding risk from an antibiotic interaction. Instead, adjust your warfarin dose based on your INR results. Most patients can continue warfarin safely with proper monitoring. Only stop it if your INR is over 10 and you’re actively bleeding - and even then, consult your doctor immediately.

How long does it take for an antibiotic to affect my INR?

It varies by antibiotic. For drugs that affect the liver (like Bactrim or ciprofloxacin), INR changes can happen within 24-48 hours. For antibiotics that kill gut bacteria (like ceftriaxone), it usually takes 3-5 days. Rifampin is the opposite - it lowers INR, and the effect builds over 7-14 days. Always check your INR 3-5 days after starting any antibiotic. Waiting longer risks missing a dangerous spike.

Can I use azithromycin instead of erythromycin if I’m on warfarin?

Yes, azithromycin is a much safer choice than erythromycin. Erythromycin strongly inhibits CYP2C9 and can raise INR significantly. Azithromycin has minimal effect on liver enzymes and is considered low-risk. Many doctors now switch warfarin patients from erythromycin to azithromycin for pneumonia or sinus infections. Always check your INR anyway - but azithromycin is the preferred macrolide when possible.

What should I do if my INR goes too high after taking an antibiotic?

If your INR is between 4.0 and 5.0 and you have no bleeding, hold your next warfarin dose and check INR again in 2-3 days. If it’s between 5.0 and 8.0, hold warfarin and take 1-2 mg of vitamin K orally - then follow up with your clinic. If your INR is above 8.0 or you’re bleeding, go to the ER immediately. Do not take vitamin K without medical advice unless instructed. Never try to correct it yourself with diet or supplements.

10 Comments

Jennifer Taylor

Okay but have you ever heard of the CIA using antibiotic-warfarin interactions to make people ‘accidentally’ bleed out? 😈 I’m not saying it’s true… but why do they never test this on people who aren’t on warfarin? Just saying. 🤔

Shelby Ume

This is one of those topics that should be mandatory in every primary care clinic. I’ve seen too many elderly patients get sent home with a new script without any warning. A simple one-page handout on warfarin-antibiotic interactions could save lives. Let’s make this standard practice, not an afterthought.

Jade Hovet

OMG YES!! My grandma almost died last year after her dentist gave her amoxicillin 😭 She didn’t even know to call her anticoag clinic! 🚨 I printed out this exact list and taped it to her fridge next to her blood thinner bottle 🏡❤️ Now she checks every med with me before taking it! #WarfarinWarrior 🙌

nithin Kuntumadugu

lol at all these ‘experts’ acting like this is some groundbreaking discovery. I’ve been on warfarin since 2012 and every doc I’ve ever had knew this. The real issue? Pharma doesn’t wanna warn people because it’d mean less prescriptions. 🤷♂️ CYP2C9? Please. They’re just hiding the truth behind ‘clinical guidelines’.

John Fred

Big shoutout to the author - this breakdown is 🔥. Especially the part about rifampin’s delayed effect. That’s the silent killer. I work in cardiology and we’ve had patients come in with strokes because their INR dropped after 10 days of rifampin. Always monitor at day 7 and day 14. And yes, ceftriaxone is sneaky - gut flora disruption is real. 💉🩸

Harriet Wollaston

I just want to say thank you for writing this. My mom had a scary episode last winter and we didn’t know why. Now I understand. I’m sharing this with everyone I know who’s on blood thinners. You’re helping people. 💛

Lauren Scrima

So… we’re just supposed to remember that ciprofloxacin = bad? But not metronidazole? Or is it the other way around? 😅 I mean, I’m just a layperson, but this list feels like a game of ‘which pill will kill me today?’

Tyrone Marshall

There’s a deeper layer here - it’s not just about drug interactions. It’s about how fragmented our healthcare system is. A dentist prescribes amoxicillin. A pharmacist fills it. The anticoag clinic doesn’t get notified. The patient doesn’t know. We’re treating symptoms, not systems. We need integrated EHR alerts. Not just ‘awareness’.

Emily Haworth

Wait… so if you’re on warfarin and take antibiotics, you’re basically playing Russian roulette with your brain? 🤯 I’m never taking another antibiotic again. Ever. I’m just gonna let the infection win. 😇

Tom Zerkoff

Thank you for this. As someone who’s been on warfarin for 8 years, I wish every prescriber had this exact list pinned to their desk. I’ve had ER docs ask me ‘What meds are you on?’ and I say ‘warfarin’ - and they still prescribe cipro. It’s terrifying. Please share this with every pharmacy school.

Write a comment