Pediatric Sleep Apnea: Tonsils, Adenoids, and CPAP Explained

What is pediatric sleep apnea?

Pediatric sleep apnea isn’t just snoring. It’s when a child stops breathing-partially or completely-dozens of times a night because their airway gets blocked. This isn’t rare. About 1-5% of all kids have it, especially between ages 2 and 6, when their tonsils and adenoids are biggest compared to their small airways. These swollen tissues physically block airflow while they sleep, leading to pauses in breathing, gasping, restless nights, and daytime tiredness. Left untreated, it can mess with brain development, stunt growth, and raise blood pressure over time.

Why tonsils and adenoids are the main culprits

Most kids with sleep apnea have enlarged tonsils and adenoids. They’re not infected-they’re just too big for the space. Think of it like a narrow hallway blocked by two large boxes. Even if the child is healthy, the physical size alone is enough to cause trouble. Research shows that when both are removed together, success rates jump to 70-80% in otherwise healthy kids. Removing just one? That often leads to the problem coming back. Doctors now know it’s not just one tissue causing the blockage-it’s both working together to squeeze the airway shut.

Adenotonsillectomy: The first-line treatment

The American Academy of Pediatrics says removing the tonsils and adenoids is the first step for most kids with moderate to severe sleep apnea. This surgery, called adenotonsillectomy, is done under general anesthesia and usually takes less than an hour. Recovery takes about a week to two, with soft foods and extra rest. Some kids feel better in just a few days. But here’s something many parents don’t know: there’s now a partial tonsillectomy option at places like Yale Medicine. Instead of removing the whole tonsil, surgeons remove only the bulk that’s blocking the airway. This cuts pain by 30-40% and reduces bleeding risks by about half. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s changing how kids recover.

When CPAP becomes necessary

Not every child gets better after surgery. About 17-73% of kids still have sleep apnea afterward, especially if they’re overweight, have neurological issues, or were born with facial differences. That’s where CPAP comes in. It’s a machine that blows gentle, steady air through a mask to keep the airway open. For kids who need it, CPAP works 85-95% of the time-if they wear it. The problem? Kids hate masks. About 30-50% of children struggle to use it every night. They feel claustrophobic, the mask leaks, or it hurts their face. The fix? Custom pediatric masks that fit small faces, and gradual training. Some kids need 2-8 weeks to get used to it. And because kids grow fast, the mask needs to be refitted every 6-12 months.

Pressure settings and how CPAP is tuned

CPAP isn’t one-size-fits-all. The pressure has to be just right-usually between 5 and 12 cm H2O for children. Too little, and the airway collapses. Too much, and it’s uncomfortable or even painful. That’s why every child needs a sleep study to find their perfect setting. This is called a titration study. It’s done overnight in a lab, with sensors tracking breathing, oxygen levels, and brain activity. The technician slowly adjusts the pressure until all the pauses stop. This isn’t guesswork. It’s science. And without this step, CPAP won’t work well.

Other options: Steroids, expanders, and new drugs

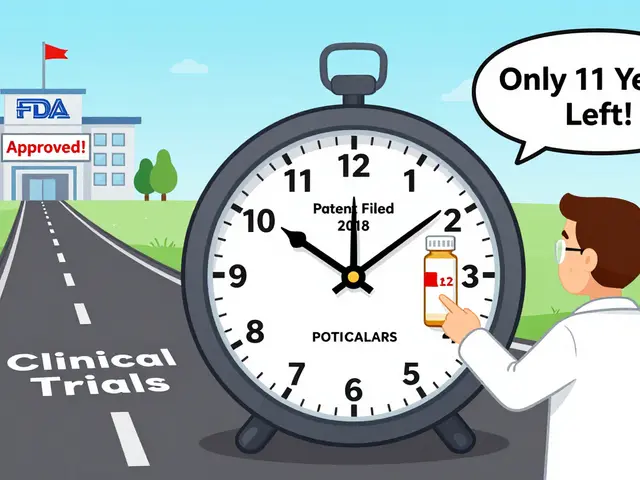

Surgery and CPAP aren’t the only tools. For mild cases, doctors sometimes prescribe nasal steroid sprays-like fluticasone-to shrink swollen tissue. It takes 3-6 months to see results, but it avoids surgery. Another option is rapid maxillary expansion, an orthodontic device that slowly widens the roof of the mouth over 6-12 months. It helps kids with narrow palates and works in about 60-70% of cases. There’s also a pill called montelukast, used for asthma, that’s being tested to reduce tonsil swelling by targeting inflammation. It’s not a cure, but it can help some kids avoid surgery. And now, a new device that stimulates the tongue nerve to keep the airway open got FDA approval for kids in 2022. It’s still rare, expensive, and only for the most complex cases.

What happens after treatment?

Even after surgery or starting CPAP, kids need follow-up. The American Thoracic Society recommends another sleep study 2-3 months after surgery to make sure the apnea is truly gone. Symptoms can return if new tissue grows back, if the child gains weight, or if they develop allergies. CPAP users need regular check-ins too. If snoring comes back, the pressure might need adjusting-or the mask might need replacing. Most issues can be fixed in a week or two with the right tweaks. The goal isn’t just to stop the breathing pauses. It’s to give the child back deep, restorative sleep so their brain, body, and behavior can catch up.

Real-life challenges: Adherence and family life

Getting a child to wear a mask every night is harder than most parents expect. One mom in Oxford told me her 5-year-old would rip the mask off every night for three weeks. They tried different masks, added stickers, made a reward chart, and finally found a soft, silicone nasal pillow that didn’t cover his nose. Now he sleeps with it without a fight. That’s the reality. Success isn’t just about the treatment-it’s about patience, creativity, and support. Families need to know they’re not alone. Pediatric sleep clinics have specialists who help kids adapt. They offer training sessions, practice nights, and even phone check-ins. The hardest part isn’t the machine. It’s changing a habit. But once the child sleeps through the night and wakes up bright-eyed, every struggle feels worth it.

11 Comments

Brian Furnell

Okay, so let me get this straight: adenotonsillectomy is first-line, but 17-73% of kids still have OSA post-op? That’s wild. And CPAP adherence is worse than a toddler’s bedtime routine. I’ve seen kids with maxillary expanders-orthodontic devices that literally widen the palate-work better than some surgeries. It’s biomechanical, not just inflammatory. The data’s there: 60-70% success with RME in narrow-palate kids. Why isn’t this standard before cutting tissue? We’re still treating symptoms, not root biomechanics.

Siobhan K.

Let’s be real-this post reads like a pharmaceutical whitepaper with a side of pediatric advocacy. Tonsillectomy is the default because it’s profitable, quick, and reimbursable. Steroid sprays? Three to six months? Who has that kind of patience when the kid’s screaming at 3 a.m.? And don’t get me started on CPAP masks that look like alien headgear. The real solution? Sleep in the same room as your kid. Physical proximity reduces apnea episodes by up to 40% in some studies. No machine. No surgery. Just presence.

Jason Silva

THEY’RE HIDING THE TRUTH. TONSILS AND ADENOIDS AREN’T THE PROBLEM-THEY’RE THE SYMPTOM. THE REAL CULPRIT? FLUORIDATED WATER. IT CAUSES TISSUE HYPERPLASIA. THE CDC KNOWS. THE AAP KNOWS. BUT THEY’RE ALL IN ON THE SURGERY INDUSTRY. CPAP? IT’S A COVER FOR THE REAL ISSUE: TOXIC ENVIRONMENTAL CHEMICALS. MY SON HAD ZERO APNEA AFTER WE SWITCHED TO DISTILLED WATER AND STOPPED USING PLASTIC BOTTLES. THEY DON’T WANT YOU TO KNOW THIS. 🤫💧

mukesh matav

Interesting read. In India, we often see kids with severe OSA due to malnutrition and chronic infections. Tonsillectomy is rare here-not because of cost, but because the tissue enlargement is often secondary to recurrent pharyngitis. We treat the infection first. Sometimes, antibiotics and steam inhalation help more than surgery. Also, CPAP machines are a luxury. Many families use simple nasal strips or elevate the head of the bed. Not perfect, but it’s what works.

Peggy Adams

So… you’re telling me I have to buy a $3,000 machine and my kid has to wear a mask that looks like a sci-fi prop every night… just so he stops snoring? I’m just gonna let him sleep with his mouth open. At least he’s breathing. 😴

Theo Newbold

Let’s analyze the data properly. The 70-80% success rate for adenotonsillectomy? That’s from studies with selection bias-only healthy, non-obese kids were included. The 17-73% failure rate? That’s the real-world number. CPAP works 85-95% of the time? Only if compliance is >80%. But compliance is 50-70%? That means actual efficacy is 42-64%. This entire field is built on inflated metrics. We’re treating marketing numbers, not physiology. And the ‘partial tonsillectomy’? It’s just a rebranding of tonsillotomy. Nothing new. Just cheaper for hospitals.

Meina Taiwo

Montelukast helps some kids. Not all. But it’s worth trying before surgery. Low risk. Low cost. Worth a 3-month trial.

Southern NH Pagan Pride

Did you know the FDA approved that tongue nerve stimulator because of lobbying from Medtronic? The clinical trials were funded by them. And the ‘sleep study’? It’s done in a lab with a weird room and wires everywhere. Kids panic. The data’s garbage. Real sleep apnea happens at home, not in a hospital. They’re diagnosing based on artificial conditions. And the ‘pressure settings’? They’re guessing. I’ve seen kids get 12 cm H2O when they needed 7. They don’t even recalibrate after growth spurts. This whole system is broken.

John Hay

I’ve seen both sides. My son had the surgery. He was better for six months. Then the snoring came back. We tried CPAP. He hated it. We switched to nasal strips. He sleeps fine now. No machine. No drama. Sometimes the simplest fix works. Don’t overcomplicate it.

Jon Paramore

Let’s talk about titration studies. They’re gold standard, yes-but here’s the catch: most pediatric sleep labs don’t use pediatric-specific algorithms. They use adult protocols. That means pressure targets are set based on adult airway resistance, not kids’. Kids have compliant airways, lower resistance. Over-titration leads to gastric insufflation, aerophagia, even gastric reflux. We’ve seen it. And nobody’s tracking it. The 5-12 cm H2O range? That’s a gross oversimplification. The real sweet spot for a 4-year-old is often 3-8 cm H2O. And it changes weekly during growth spurts. This isn’t just science-it’s precision medicine. We’re treating kids like small adults. And it’s dangerous.

Swapneel Mehta

My cousin’s daughter had OSA after a bad cold. They tried sprays first. Took four months, but she’s now snore-free. No surgery, no mask. Just patience and a humidifier. It’s not glamorous, but it works. And honestly? The best thing for these kids isn’t a machine or a scalpel-it’s a quiet room, no screens before bed, and a consistent routine. Sleep hygiene matters more than we admit.

Write a comment