Thoracentesis: What It Is, Why It’s Done, and What to Expect

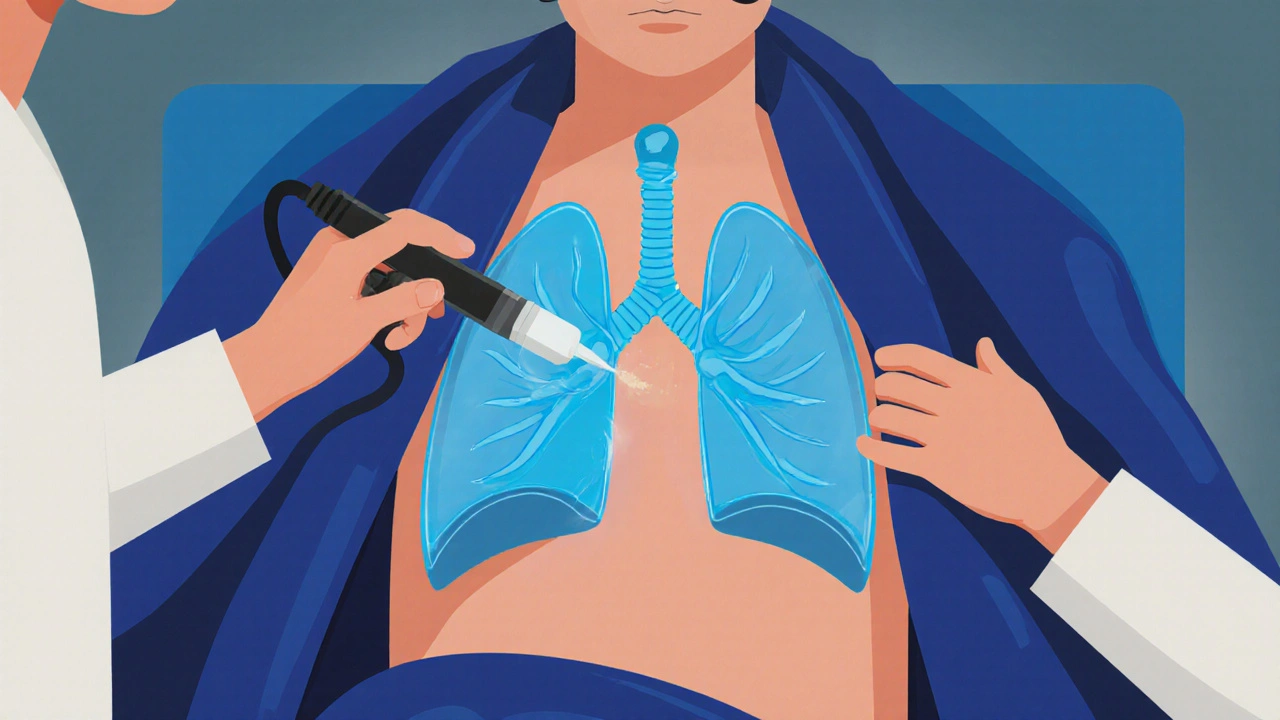

When fluid builds up around the lungs—called a pleural effusion, an abnormal collection of fluid in the space between the lungs and chest wall. Also known as fluid around the lung, it can make breathing difficult, cause pain, and signal something more serious like infection, heart failure, or cancer. That’s where thoracentesis, a minimally invasive procedure to drain excess fluid from the pleural space. It’s also called pleural tap, and it’s one of the most common diagnostic and relief procedures in pulmonology and critical care. This isn’t surgery. No big incisions. No overnight stay. Just a thin needle, guided by ultrasound, to pull out the fluid that’s pressing on your lungs.

Doctors use thoracentesis for two main reasons: to find out what’s causing the fluid buildup, and to help you breathe easier. If you’ve been feeling short of breath, especially when lying down, or have a persistent dry cough with chest pressure, this test might be the next step. The fluid they collect gets sent to a lab—checking for infection, cancer cells, protein levels, or signs of heart failure. In some cases, removing just a cup of fluid can make you feel like you’ve taken off a heavy coat. But it’s not just about comfort. Too much fluid can collapse part of the lung, and leaving it untreated can lead to scarring or infection like empyema.

People who’ve had pneumonia, heart failure, or certain cancers—especially lung, breast, or lymphoma—are most likely to need this. It’s also common in older adults or those with kidney disease. But it’s not just for the elderly. Even younger people with autoimmune diseases like lupus can develop pleural effusions. The procedure itself takes less than 30 minutes. You sit up, lean forward, and the area is numbed. You might feel pressure, maybe a brief pinch, but not sharp pain. Afterward, you’ll get a chest X-ray to make sure your lung didn’t collapse. That’s rare, but it’s why ultrasound guidance is now standard.

Some patients worry about the risks. The biggest one? A collapsed lung, which happens in less than 5% of cases. Minor bleeding or infection at the needle site is possible but uncommon. Most people go home the same day. No stitches. No pain pills needed beyond maybe acetaminophen. You’ll be told to avoid heavy lifting for a day or two, but you can usually walk, eat, and sleep normally right after.

What you won’t find in most doctor’s offices is how often this simple procedure changes everything. One patient, a 68-year-old retired teacher, had been told her shortness of breath was just "aging." Thoracentesis revealed cancer cells in the fluid. She started treatment early. Another, a 42-year-old with unexplained swelling, found out her heart wasn’t pumping right—fluid drained, symptoms vanished within hours. These aren’t rare stories. They’re routine.

Below, you’ll find real patient experiences, comparisons with other procedures like chest tubes, and guides on what happens after the fluid is removed. Whether you’re preparing for thoracentesis, supporting someone who is, or just trying to understand why it’s done, the posts here cut through the jargon and give you what matters: clear facts, practical advice, and what to ask your doctor next.

Pleural Effusion: Causes, Thoracentesis, and How to Prevent Recurrence

Pleural effusion causes breathing trouble due to fluid around the lungs. Learn the main causes, how thoracentesis works with ultrasound guidance, and proven ways to prevent it from coming back-based on the latest medical guidelines.

Read More