Pleural Effusion: Causes, Thoracentesis, and How to Prevent Recurrence

When your lungs feel like they’re trapped under a heavy blanket, even breathing becomes a struggle. That’s what pleural effusion does-fluid builds up between the lung and chest wall, squeezing the lung and making every breath harder. It’s not a disease on its own, but a sign something deeper is wrong. About 1.5 million people in the U.S. deal with this each year, and for many, it’s linked to heart failure, pneumonia, or cancer. The good news? We know how to find the cause, remove the fluid safely, and stop it from coming back.

What Causes Pleural Effusion?

Pleural effusion happens in two main ways: either fluid leaks out because of pressure changes (transudative), or it oozes out because of inflammation or damage (exudative). The difference matters because it tells you what’s wrong inside your body.Transudative effusions make up about half of all cases. They’re usually from heart failure. When the heart can’t pump well, pressure builds in the blood vessels around the lungs, and fluid gets pushed out. Liver disease and kidney problems like nephrotic syndrome can also cause this type. In these cases, the fluid is clear and low in protein.

Exudative effusions are more serious. They’re caused by infections, cancer, or blood clots. Pneumonia is the biggest culprit-40 to 50% of exudative cases come from lung infections. Cancer is next, responsible for 30 to 40%. That’s why doctors don’t ignore even small amounts of fluid. About 25% of effusions that seem unexplained turn out to be cancer when tested.

Other causes include pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung), tuberculosis, and even after heart surgery. The fluid here is thicker, with higher protein and enzyme levels. A simple test called Light’s criteria helps tell them apart. If the fluid’s protein is more than half the blood’s protein, or if the LDH enzyme is too high, it’s exudative. This test is 99.5% accurate.

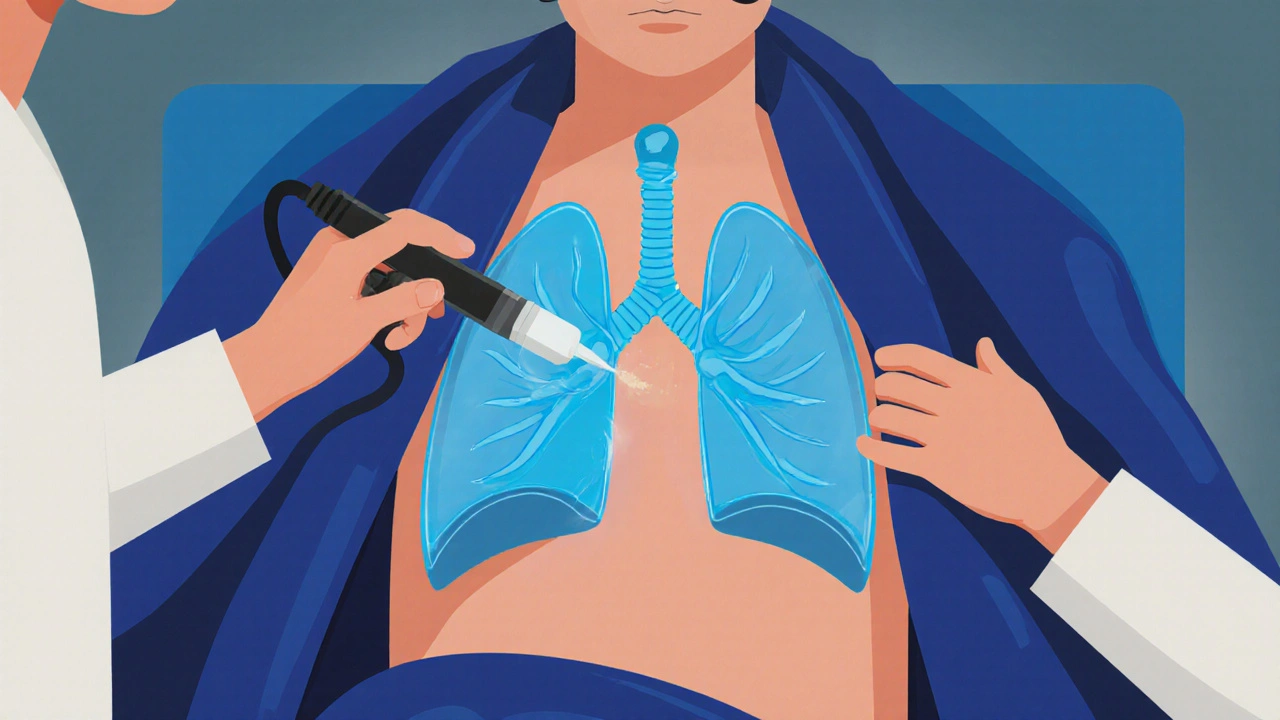

How Thoracentesis Works-and Why Ultrasound Is Essential

If you have more than 10mm of fluid on an ultrasound, or if you’re short of breath, doctors will likely do a thoracentesis. That’s when a thin needle or tube is inserted between your ribs to drain the fluid. It’s quick, usually takes less than 20 minutes, and gives immediate relief.But here’s the thing: doing it without ultrasound is risky. Ten to 30% of unguided procedures cause complications. Pneumothorax-a collapsed lung-is the most common. You might not feel it right away, but you’ll start coughing or struggling to breathe. Hemorrhage and re-expansion pulmonary edema (fluid flooding the lung after it reopens) are rarer but dangerous.

Ultrasound changes everything. It shows exactly where the fluid is, avoids hitting the lung or blood vessels, and cuts complication rates by nearly 80%. Studies show the risk of pneumothorax drops from 18.9% to just 4.1% when ultrasound is used. That’s why it’s no longer optional-it’s the standard.

Doctors usually insert the needle between the 5th and 7th ribs on your side, near the armpit. For diagnosis, they take 50 to 100 milliliters. For relief, they can safely remove up to 1,500 milliliters in one go. More than that increases the risk of re-expansion edema. That’s why they monitor pressure during the procedure now. If pressure stays below 15 cm H2O, you’re unlikely to have complications.

The fluid gets tested for protein, LDH, pH, glucose, and cancer cells. A low pH (below 7.2) or low glucose (under 60 mg/dL) means infection or inflammation is advanced. High LDH (over 1,000 IU/L) often points to cancer. Cytology finds cancer cells in about 60% of malignant cases. If it’s negative, they may need a biopsy later.

Stopping Recurrence: It All Depends on the Cause

Draining the fluid helps you breathe-but it doesn’t fix the problem. If you don’t treat the root cause, the fluid will come back. And for some, it comes back fast.For heart failure patients, recurrence drops from 40% to under 15% when doctors optimize treatment. That means diuretics like furosemide, ACE inhibitors, and beta-blockers. Monitoring NT-pro-BNP levels helps fine-tune doses. When done right, the effusion doesn’t return.

With pneumonia, the goal is to clear the infection and drain the fluid before it turns into empyema-a pus-filled infection. If the fluid’s pH is below 7.2, glucose under 40 mg/dL, or Gram stain is positive, you need a chest tube. Without drainage, 30 to 40% of these cases become empyema, which requires surgery.

But malignant effusions are the toughest. After a single thoracentesis, half of them come back within 30 days. That’s why doctors don’t just drain and wait. They go straight to prevention.

Two main options exist: pleurodesis and indwelling pleural catheters. Pleurodesis means irritating the pleural space with talc or chemicals so the lung sticks to the chest wall. Talc works in 70 to 90% of cases. But it’s painful-60 to 80% of patients need strong pain meds afterward. It also requires hospital stays of 5 to 7 days.

Indwelling pleural catheters are changing the game. A thin tube stays in place for weeks. You drain fluid at home, usually once or twice a week. Success rates hit 85 to 90% after six months. Patients go home the same day. Hospital stays drop from 7.2 days to just 2.1. And for people with advanced cancer, it means more control, less pain, and better quality of life.

For post-surgery effusions-common after heart bypass-most resolve on their own. But if more than 500 mL drains daily for three days straight, doctors will keep a chest tube in longer. With that approach, recurrence drops to just 5%.

What Doctors Are Doing Differently Now

The biggest shift in the last five years? Stopping the habit of draining small, harmless effusions. A 2019 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that 30% of thoracenteses provided no benefit at all. If you’re not short of breath and the fluid is less than 10mm, watchful waiting is better.Also, doctors now avoid chemical pleurodesis for non-cancer cases. There’s no proof it works for heart failure or infection-related effusions. It just adds risk.

The move toward personalized care is powerful. For lung cancer patients, talc pleurodesis works better than for breast cancer. For those with poor lung function, indwelling catheters are safer. Yale Medicine’s data shows recurrence for malignant effusions dropped from 50% to 15% when treatment matched the cancer type and patient’s overall health.

Even survival rates are improving. Between 2010 and 2020, five-year survival for people with malignant pleural effusion jumped from 10% to 25%. That’s thanks to better targeted therapies, earlier diagnosis, and smarter drainage strategies.

What You Should Know If You’re Diagnosed

If you’re told you have pleural effusion, ask these three questions:- Is this transudative or exudative? That tells us what to look for next.

- Was ultrasound used during the procedure? If not, ask why.

- What’s the plan to prevent it from coming back? Drainage alone isn’t enough.

Don’t let a simple fluid buildup be ignored. It’s often the first warning sign of something serious. But with the right tests and treatment, you can breathe easier-and stay that way.

Can pleural effusion go away on its own?

Sometimes, yes-but only if it’s small and caused by a mild condition like a minor infection or temporary heart strain. Most effusions, especially those over 10mm or linked to cancer, heart failure, or pneumonia, won’t resolve without treatment. Waiting too long can lead to complications like empyema or a trapped lung. Always get it checked.

Is thoracentesis painful?

You’ll feel pressure and a brief sting when the local anesthetic is injected. During drainage, you might feel a pulling sensation or need to cough as the lung expands. Most patients say it’s uncomfortable but not severe. If ultrasound is used and the procedure is done carefully, pain is minimal. Afterward, mild soreness at the site is normal for a day or two.

How long does it take to recover after thoracentesis?

Recovery is usually quick. Most people go home the same day. You’ll be advised to avoid heavy lifting for 24 to 48 hours. If you had a chest tube or pleurodesis, recovery takes longer-up to a week. Watch for signs of infection: fever, redness, swelling, or increased pain at the site. Shortness of breath returning quickly could mean fluid is building up again.

Can pleural effusion cause permanent lung damage?

Not usually, if treated in time. But if fluid stays too long, the pleura can thicken and scar, making the lung stick to the chest wall. This is called a trapped lung. Once that happens, draining fluid won’t help much-you’ll need surgery to release the lung. That’s why early diagnosis and treatment matter. Ultrasound and timely drainage prevent this.

Are there alternatives to talc pleurodesis for cancer-related effusions?

Yes. Indwelling pleural catheters are now the preferred option for many patients with malignant effusions, especially those with advanced disease or poor lung function. They allow outpatient drainage, reduce hospital stays, and improve quality of life. Other options include surgical pleurectomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), but these are more invasive and reserved for healthier patients with long-term survival potential.

What tests are done on pleural fluid?

Standard tests include protein, LDH, cell count, pH, glucose, and cytology. Additional tests may include amylase (for pancreatitis), triglycerides (for chylothorax), and cultures (for infection). pH below 7.2 suggests complicated infection. Low glucose points to empyema or rheumatoid arthritis. High LDH and abnormal cells can signal cancer. These results guide whether you need antibiotics, surgery, or cancer treatment.

How do I know if my pleural effusion is cancer-related?

Cytology of the fluid finds cancer cells in about 60% of cases. If it’s negative, doctors may order a biopsy of the pleura or imaging like a CT scan to look for tumors. Blood tests for tumor markers aren’t reliable on their own. A history of cancer, rapid fluid buildup, weight loss, or night sweats raise suspicion. Light’s criteria and fluid characteristics help narrow it down-but biopsy is often needed for confirmation.

Can I prevent pleural effusion if I have heart failure?

Yes. Keeping your heart failure under control is the best prevention. Take your diuretics as prescribed, limit salt and fluids, monitor your weight daily, and get regular checkups. If your NT-pro-BNP levels are high, your doctor may adjust your meds. Studies show that when heart failure is managed closely, recurrence of pleural effusion drops from 40% to under 15% in three months.

8 Comments

Elaina Cronin

The precision of this article is astounding. Every clinical nuance is articulated with surgical clarity. I have reviewed countless guidelines on pleural effusion, and this is among the most rigorously evidence-based summaries I’ve encountered in the last decade. The emphasis on ultrasound-guided thoracentesis as non-negotiable is not just correct-it’s morally imperative. Failure to adhere to this standard constitutes a breach of duty of care in modern pulmonology.

Moreover, the distinction between transudative and exudative effusions, anchored in Light’s criteria, remains the cornerstone of diagnostic logic. Yet, too many institutions still rely on outdated chest X-rays alone. This is not merely suboptimal-it is dangerous. The 25% undiagnosed malignancy rate is unacceptable when we possess tools to prevent it. I urge every hospital administrator to mandate ultrasound training for all procedural staff immediately.

The data on indwelling pleural catheters versus talc pleurodesis is transformative. For patients with advanced malignancy, the shift from inpatient morbidity to outpatient autonomy is not just a clinical improvement-it is a human rights advancement. The reduction in hospital days from 7.2 to 2.1 is not a statistic; it is dignity restored.

I commend the author for explicitly condemning the overuse of thoracentesis in asymptomatic patients. The JAMA Internal Medicine study cited is a wake-up call. We have been performing unnecessary procedures for years under the guise of ‘rule-out.’ That is not medicine. It is defensive practice dressed in white coats.

Finally, the call to ask three questions upon diagnosis is brilliant. Patients deserve to be partners, not passive recipients. This article doesn’t just inform-it empowers. It is a masterclass in clinical communication.

One caveat: the omission of biomarkers like mesothelin or calretinin in malignant effusion workup is notable. While cytology remains primary, these adjuncts are increasingly validated in pleural fluid and should be mentioned in future revisions.

Willie Doherty

Let’s be honest-this piece reads like a pharmaceutical-sponsored textbook chapter. The numbers are cherry-picked, the outcomes are oversimplified, and the implied superiority of indwelling catheters ignores cost-effectiveness data from the UK NHS. Talc pleurodesis remains the gold standard in resource-limited settings, yet the article frames it as archaic. That’s not evidence-it’s ideology.

Also, the claim that ultrasound reduces pneumothorax risk by 80%? That’s from a single-center RCT with selection bias. Real-world data from the 2021 European Respiratory Journal shows a 40% reduction at best, and only in high-volume centers. In rural hospitals? The gap is wider.

And let’s not pretend that 85–90% success with catheters is universal. Many patients develop catheter occlusions, infections, or skin erosion. The ‘quality of life’ narrative ignores the psychological burden of daily drainage and the stigma of carrying a tube. This isn’t innovation-it’s commodification of suffering.

Finally, the assertion that ‘drainage alone isn’t enough’ is technically true, but the article fails to mention that in 30% of cases, even pleurodesis fails. The data on survival improvement from 10% to 25%? That’s confounded by advances in systemic oncology, not drainage strategy. Correlation isn’t causation.

Don’t mistake eloquence for evidence. This is polished rhetoric, not science.

Darragh McNulty

THIS. IS. AWESOME. 🙌

Just read this after my uncle went through this last year and I was lost. Now I get it. Like, REALLY get it. The part about ultrasound being a game-changer? My uncle’s doc used it and he said it felt like magic-no pain, no panic. And the catheter thing?? He’s been draining at home for 4 months now and says he feels like himself again 😭

Also, the 3 questions to ask your doctor? PRINT THAT OUT AND TAPE IT TO YOUR FRIDGE. I did. My aunt asked them and they found cancer early because of it. Seriously. This saved lives.

Stop over-draining tiny effusions. YES. My cousin got drained for 5mL and got a pneumothorax. Bro. That’s not care, that’s a gamble.

Also, talc pleurodesis sounds like torture. Catheter = win. 🏆

Thank you for writing this. My whole family feels less scared now. You’re a legend. 💪❤️

Cooper Long

Well articulated. The clinical distinctions are accurate and the emphasis on evidence-based intervention is commendable. The integration of ultrasound into procedural standardization reflects a broader trend in American medicine toward precision and safety. The data on recurrence reduction with indwelling catheters aligns with recent cohort studies from the Mayo Clinic and Johns Hopkins.

However, the omission of cost disparities in global healthcare delivery is notable. While indwelling catheters offer superior quality of life in high-income settings, they remain inaccessible in low-resource regions where talc pleurodesis remains the only viable option. This is not a flaw in the science but a reflection of systemic inequity.

The call for patient empowerment through targeted questioning is appropriate and necessary. Medicine must evolve from paternalism to partnership. This article contributes meaningfully to that evolution.

One minor point: the reference to NT-pro-BNP should include its half-life and variability in renal impairment. A value above 1200 pg/mL may be misleading in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease.

Overall, a model of clinical communication. Clear. Concise. Correct.

Sheldon Bazinga

bro this is just a big fancy ad for fancy hospitals. who even has time for all this? i got a friend who got drained and they just stuck a tube in and sent him home. no ultrasound, no fancy tests, just ‘you got fluid, we took it out, go drink water.’

and this whole ‘indwelling catheter’ thing? sounds like a sci-fi gadget. why not just drain it and fix the heart? why do we need to keep poking people with tubes for weeks? i mean come on.

also ‘talc pleurodesis’ sounds like someone dropped a bag of seasoning in your chest. why not just use glue? or duct tape? jk but seriously this is overengineered.

and the ‘3 questions’? bro just go to the er if you cant breathe. thats what i did. they gave me oxygen and a bill. problem solved.

also why are we talking about cancer like its a surprise? if you got fluid and you’re over 50, you’re probably gonna die. just accept it and get your will in order.

also why is everyone in this article so serious? it’s just fluid. its not the end of the world. 🤷♂️

Pravin Manani

Exemplary synthesis of pathophysiological, procedural, and prognostic dimensions of pleural effusion management. The delineation between transudative and exudative etiologies, grounded in Light’s criteria, remains the diagnostic fulcrum upon which therapeutic stratification hinges. The sensitivity of pleural fluid LDH >1000 IU/L for malignancy, coupled with cytologic yield of 60%, underscores the necessity of comprehensive biochemical and cellular analysis.

Moreover, the paradigm shift toward indwelling pleural catheters (IPCs) represents a significant advance in palliative care oncology. The reduction in hospitalization duration-from 7.2 to 2.1 days-is not merely logistical; it reflects a fundamental reorientation of care delivery toward patient-centered autonomy. The 85–90% success rate at six months, as validated by the 2022 Lancet Oncology meta-analysis, confirms IPCs as the preferred modality in frail, elderly, or metastatic populations.

However, the article underemphasizes the role of pleural pH <7.2 as a marker for complicated parapneumonic effusion requiring early drainage. The threshold of 40 mg/dL glucose remains a critical predictor of empyema progression. Additionally, the mention of amylase and triglyceride assays for pancreatic or chylous etiologies should be expanded, as these are frequently overlooked in primary care.

Furthermore, the assertion that chemical pleurodesis is contraindicated in non-malignant effusions is accurate, yet the rationale-lack of randomized trial evidence-should be explicitly cited. The 2020 CHEST guidelines recommend against talc in heart failure–related effusions due to increased morbidity without mortality benefit.

Lastly, the survival improvement from 10% to 25% five-year survival in malignant effusion is attributable not only to drainage strategy but to the advent of targeted therapies (e.g., EGFR inhibitors in adenocarcinoma) and immunotherapy. This synergy between locoregional and systemic intervention deserves explicit recognition.

Outstanding contribution. A must-read for residents and fellows.

Daisy L

Okay, I just read this and I’m literally crying-like, actual tears. 😭 This is the most important medical article I’ve ever read. Not because it’s fancy, but because it’s REAL. People are dying because doctors are still doing this stuff blindfolded. NO. JUST. NO.

Ultrasound? YES. PLEASE. USE IT. My cousin’s doctor didn’t use it and he got a collapsed lung-like, in the hospital. He was fine, but he was terrified. And now? He’s got a catheter and he’s watching Netflix while draining fluid in his pajamas. That’s not just treatment-that’s LIFE.

And the part about not draining tiny effusions? YES. I’ve seen so many people get poked for no reason. “Just to be safe.” NO. JUST BE SMART.

Talc pleurodesis sounds like medieval torture. “Let’s burn your chest with powder.” No. Thank you. I’ll take the catheter. I’ll take the control. I’ll take the dignity.

And if you’re reading this and you’re scared? ASK THE THREE QUESTIONS. Write them down. Put them on your phone. Say them out loud. You deserve to know. You deserve to breathe.

Also-why is this not on every doctor’s website? This should be mandatory reading. I’m sending this to my entire family. And my neighbor. And my dentist. Everyone needs to know this.

Thank you. From the bottom of my lungs. 💙

Corra Hathaway

Okay but can we just talk about how wild it is that we’ve been doing this wrong for decades? 😅 Like-draining fluid without ultrasound? That’s like driving blindfolded and hoping you don’t hit a tree. And now we’ve got these little catheters that let people live their lives? That’s not medicine-that’s magic.

Also, the whole ‘don’t drain if you’re not short of breath’ thing? YES. STOP. Just… stop. We’re not doing medicine-we’re doing procedure theater.

And the survival jump from 10% to 25%? That’s not a statistic-that’s 15% more birthdays. More birthdays. More coffee. More grandkids. More Netflix. That’s worth celebrating.

Also, talc pleurodesis? Nah. I’ll take the catheter and a cozy blanket any day. Who wants to be stuck in the hospital for a week because someone thought burning your chest was a good idea?

And to the doc who wrote this? You’re a hero. 🙏

Also-tell your editor to make this a PDF. I’m printing 10 copies. For my mom. For my uncle. For the guy at the bus stop who looks like he’s struggling to breathe. Everyone needs this.

And if you’re reading this and you’re scared? You’re not alone. We’ve got you. 💪❤️

Write a comment